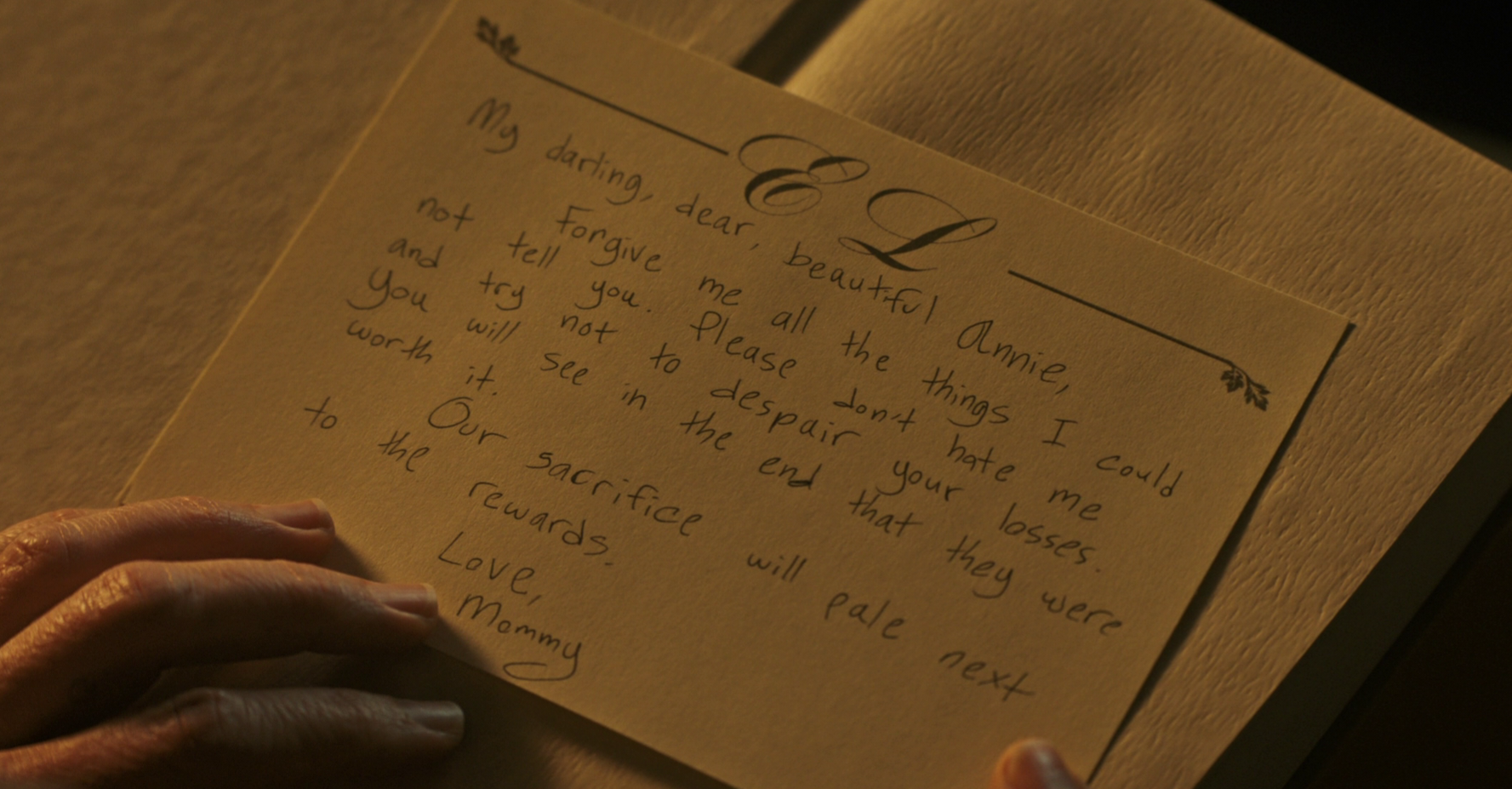

The Conjuring, The Witch, Sinister, The Babadook, – all explored similar themes in albeit in their own unique ways- about the passing down of familial horrors and trauma, grief, panic, sin, murder, through a conductor of some sort, dolls, homes, farm animals, necklaces. There is always a passageway for evil in these films. Some door opened by curiosity, innocence/naivety, or vanity, in the case of Hereditary it’s avoidance as a coping mechanism. But, where those movies provide catharsis, closure (if only until the next movie) and safety from the damnation of these experiences and emotions, Aster’s provides no such release. In this way it shares cinematic bloodlines with films like Polanski’s “Rosemary’s Baby”, Andrzej Żuławski’s “Possession”, and Phillip Kaufman’s paranoid invasion fantasy “Invasion of the Body Snatchers”. All of these films in some way explored the corruption of bonds and bodies by insidious forces from within and without. For the Graham family and especially it’s central character Annie (Toni Collette in a raw, slowly unhinged, barn burner of a performance) it’s communication from within the very American tradition of tying sacrificial suffering to success. By the time we arrive at possibly the most traumatic event of the film – a scene that is grounded in familial terror rather than the supernatural, – we know there’s a history uncovered. The hardships of parenthood, marriage, the masked truth about many of our so called sacred bonds, blood thicker than water and the like, and the made up importance of a patriarchal male lineage. You not only have the implicit and explicit idea that this family struggles with secrets, (The eulogy Annie gives at her mother's funeral) or patriarchal attitudes as it concerns both lineage, and treatment ( The father son relationship, and the grandmother’s “wish”) but there is an unsaid economic concern, (the work place calls) and the desire to attain status and riches (Paimon and his gifts here can easily stand in for capitalism) we can feel the stressors, and we are faced with a grim reality; Hereditary is a dark fairy tale about deconstructing the fairy tales around family. It is as unrepentant about what it might conjure in us, as the forces who work from just outside the parameters of the story are about their roles in an entire family’s harm , and it is eerie, unnerving, upsetting, and difficult to watch for that reason