Gene Hackman : Everyday Magic.

/I once told a friend that if I tried to write about Gene Hackman, I feared I might never stop…I guess today I must put that then hypothetical to its test. Hackman at the very ripe and towering age of 95 years has died ending a towering career in what seems to be very mysterious causes despite his age when factoring in the death of his wife, and strangely enough, his dog. It is a rather abrupt and unfitting end to a man of his stature, but then what end is fitting for someone who has been and done as much for any field or discipline as Hackman has been or done for acting! And what end can I bring to any scrawling about of such a massive figure?

My first encounter with Gene Hackman cannot easily be remembered, my best guess would be Richard Donner’s “Superman”, or Roger Donaldson’s “No Way Out”. The latter was an HBO mainstay when I was a kid, and one of the few “grownup” films I was allowed to watch. The summer in Blythe, California was oppressive. Temperatures rose to well over 100 degrees regularly, and going outside to play (then a common occurrence) was quite literally trial by fire. So, many an hour was spent in the air conditioned home of my grandmother alternating between her soap operas and my cartoons and then whatever was on cable. I watched “No Way Out” anytime it was on, it was less an obsession and more an instinct. I was drawn to the ominous electronic-like sounds of Maurice Jarre's score, the beauty of the naval whites, and Kevin Costner's “high and tight”, and to Gene Hackman’s curly sunroof of a mane and the face that hung beneath it. I liked watching him rock that silly toupee in “Superman”, even when I didn't recognize that the comedy was intentional. In retrospect that role faltered because Lex Luthor is not a great fit for what Hackman does best. Luthor may be human, but he's not an everyman, he is a genius and “The world’s greatest criminal mastermind”. To fit him onto Hackman’s blue-collar frame they had to parody him. Didn't matter though, because Hackman wasn't yet an actor to me- he was more like a showman. A kind of clown your folks hire to amuse you from behind a screen when they need a break from your incessant hanging about. I didn't truly meet the actor or understand the draw until 1992’s “Unforgiven”. Already by then a Western aficionado by way of my father's influence, I was drawn to the film upon release of its trailer. Already pretty well converted into the church of Eastwood, he was the central draw of the film, but once I saw the movie it was Hackman's “Little Bill Daggett” that walked away with it. Daggett was an interesting figure, he was more than just “mean” even to the over simplified mind of a 13 year old me. He was magnetic, complex, agitated, cruel, and funny. Saul Rubinek’s weasel-like wanna be auto-biographer-stenographer W.W. Beauchamp’s interest in him felt warranted even from under a gun. Bill was incredulously charming considering he was a steaming pile of excrement, and he moved with an ease heretofore never seen before by little ol me. That observation is maybe the central tenent of my rather impromptu thesis on this titan. In my favorite scene, Hackman's Daggett has rather merrily secured Beauchamp’s services after viciously beating and jailing his previous employer “English Bob” (a fantastic Richard Harris) and midway through his pedantic diatribe on the import of a steady mind over a quick draw in a gunfight, decides on a whim to put on an impromptu demonstration of his theory. The turns this scene takes are exemplary of exactly the skill with which Hackman makes the most complex and ambiguous work look as simple as eating a slice of warm apple pie.

Hackman's Bill is at first laying down while relaying all this wisdom to Beauchamp, as he gets into the details of his philosophy he excites himself, and as he gets excited he comes mysteriously to the decision to give Beauchamp a gun. Hackman for his part intelligently buries the lead under a barrage of charm. He opens the drawer and plops the gun onto the desk without so much as a glance at it, “Look here, take that” before he's back down head almost fully submerged in another drawer looking for keys. “Go on, take it”. He says this with the same assertive optimism of an infomercial salesman. The “sham wow” guy getting ready to show you just how much water his novelty rag can soak up without losing its dryness. Once he finds them, the keys to Bob's cell join the gun and he now surprisingly instructs Beauchamp to shoot him and he and Bob will be free. We the audience know this is too good to be true, and so does Beauchamp, but Hackman’s aplomb and streamlined delivery assuages the two of us, it serves as a veritable magic trick, allows us to convince ourselves of the impossible. Beauchamp scoffs, stumbling over his tongue “It isn’t…is it loaded?” Hackman's reply is instantaneous, and the inflection of warmth hasn't moved one degree in temperature - “Wouldn't do you much good if it wasn't” “First you gotta cock it” - he instructs as if teaching a child to ride a bike. Beauchamp is in patient disbelief, Harris’s English Bob previously mired in silent defeat, now sits up, himself caught at the intersection of disbelief and bewilderment. “Now you got to point it”. Rubinek makes every decision to follow through with an instruction a visceral exercise in anxiety, which only serves to further the mystery behind what exactly it is Daggett is up to set against Hackman's flaccid informality, that is until..”Go on point it”. This is the first line delivery Hackman gives that has something of a menace underneath it. It's the first clue that this is not merely a demonstration at a science fair, a confirmation of a hypothesis, but something else entirely. It's firm and curt, and bares the teeth of a threat. “Now all you got to do is pull the trigger”. Hackman’s face is a complete mystery. Bill’s actions up to this point have informed us he will shoot them both, but he hasn't so much as moved, and if his body hasn't moved, then we at least should be able to look to something in his face, in his eyes. Hackman’s Bill -normally a showman, gives us nothing. It confuses us every bit as much as it confuses poor old Beauchamp. The physical silence of his face is as important as that of the lack of words, and then he suddenly and abruptly breaks it, falling right back into his arresting charm. He chuckles, “Hot ain't it”. Maybe my favorite action in this favorite scene is Hackman rubbing his face as he says “You ain't even put your finger on the trigger”. Mouth wide open as he slides his index finger down from his nose to his upper lip. That movement is an affirmation of the ease with which Hackman worked. His dedication to the truth of any scene, any moment, every moment. Nothing for Hackman was about pomp and excess, he was always lean, always -to purposely pun - “Prime Cut”.

Robert DeNiro once said “Be in the moment. Period. Just be there. Because if you get all like, ‘Oh I got to do this big thing.’ It just never works. It just doesn’t work. You’ve just got to let go. If it happens, it happens. If it doesn’t, it doesn’t. Whatever you do is ok, just be truthful, honest, real, and that’s all you can ask for.” It certainly meets the bulk of DeNiro’s career as an actor, but it is the entirety of Hackman's. Hackman always seemed to just be doing things. You know his prep had to be vicious, because the results were always of the unconscious type. I liked to say alot that every character Hackman played, every role he encountered, he stepped into it as if he was Mr Rogers. Taking off his professional blazer and trading it in for a casual cardigan, dress shoes for a comfy pair of loafers. Every piece of furniture in any movie he was in seemed figuratively imported directly from his house, the way he moved around it, or in it. In “No Way Out” he plays the nefarious Secretary of Defense “David Brice”. Hackman is notably not Little Bill in this. He could hardly be less tough, a little less cruel, far more vulnerable. I once wrote to the effect that his confidence goes in and out like a bad accent, but what does remain is that ease around a room. In his opening meeting with Kevin Costner he makes his blocking look alot more like it should be called rounding. There are no jagged edges, no “herk” and no “jerk”, every movement flows seamlessly into the next and feels as natural as breathing. He rolls a piece of paperwork in his hand. When his feet take up residence on his desk the arrive there the same way a paper plane seems to sit on air. As he's acting, he takes a call, and his stalls to hold as he speaks to Costner might as well be your mother. Everything he does is pure veracity, there is no affect. In 95’s “Crimson Tide”, he calls in Denzel’s Ron Hunter for a meeting, before he gets to his point, Hackman takes off his cap and rubs his head, they've not actually been in that boat for hours on days, but Hackman's organic note there implies as much, it not only serves to reinforce the illusion of reality, but to show just exactly the level of unconscious comfort Hackman frequently displayed for years over his stories career. In “The Royal Tenenbaums” he sits there in this cramped sardine can of a kitchen dining booth, smoking with the lived in non-chalance of a man whose seen every corner of his home for well over 60 years so his head goes nowhere it isnt needed. As beatific, extravagantly architectural and well put together as the movie is Hackman counters with a dress free uncomplicated, complicated performance. In short Hackman is a magician.

In Christopher Nolan’s “The Prestige” there is a constant refrain that the fundamental object of magic, and thusly a magician - is to make the ordinary extraordinary, and then to make the extraordinary astonishing, that was what Hackman was to me, to us, to the craft. Intentional or not, like Nolan himself, Hackman understood on a near metaphysical level, that the power of this medium, this discipline, is in making a spectacle of the mundane. This brings me back to the second half of the aforementioned scene in “Unforgiven”, where after Hackman has made the tension disappear, he brings it back. Beauchamp is the instigator, of this event, but Bill is going to finish it. When Beauchamp asks what would happen were he to give the gun to English Bob, Hackman doesn't blink, literally or figuratively. “Give it to him” he clips. As Beauchamp slowly and carefully guides the gun towards Bob, and Bob cautiously moves towards it, Hackman now reveals the threat that lived under it all along. His eyes, face and neck finally move, and the implication is clear, Bob is a deadman if he so much as touches it. This is not the reveal of merely the threat, but the motivation that up until then had been somewhat mysterious. The buried lead? - This was not merely a demonstration of proof of philosophy, but of power. This is the big “tadah”. Like the sawed woman we know the impossible was not possible, the trick was to allow us to give in to fooling ourselves for just long enough to arrive at some joy, some sense of wonder, of astonishment. “You don't really want to know. You want to be fooled. But you wouldn't clap yet. Because making something disappear isn't enough; you have to bring it back.” explains Michael Caine's character John Cutter in The Prestige - this was an essential trait of Hackman’s magic, to being us back from the brink. To have us question, to interrogate, good and evil, to bring us back to ourselves. Hidden in every one of his mostly every-men, and his supposed simplicity, was the extraordinary in us. The way that he worked, the way he executed was vital to the creation of a career steeped in the magic of the everyday, and that was his legacy and that is his magic. RIP

Cool is All You Need.

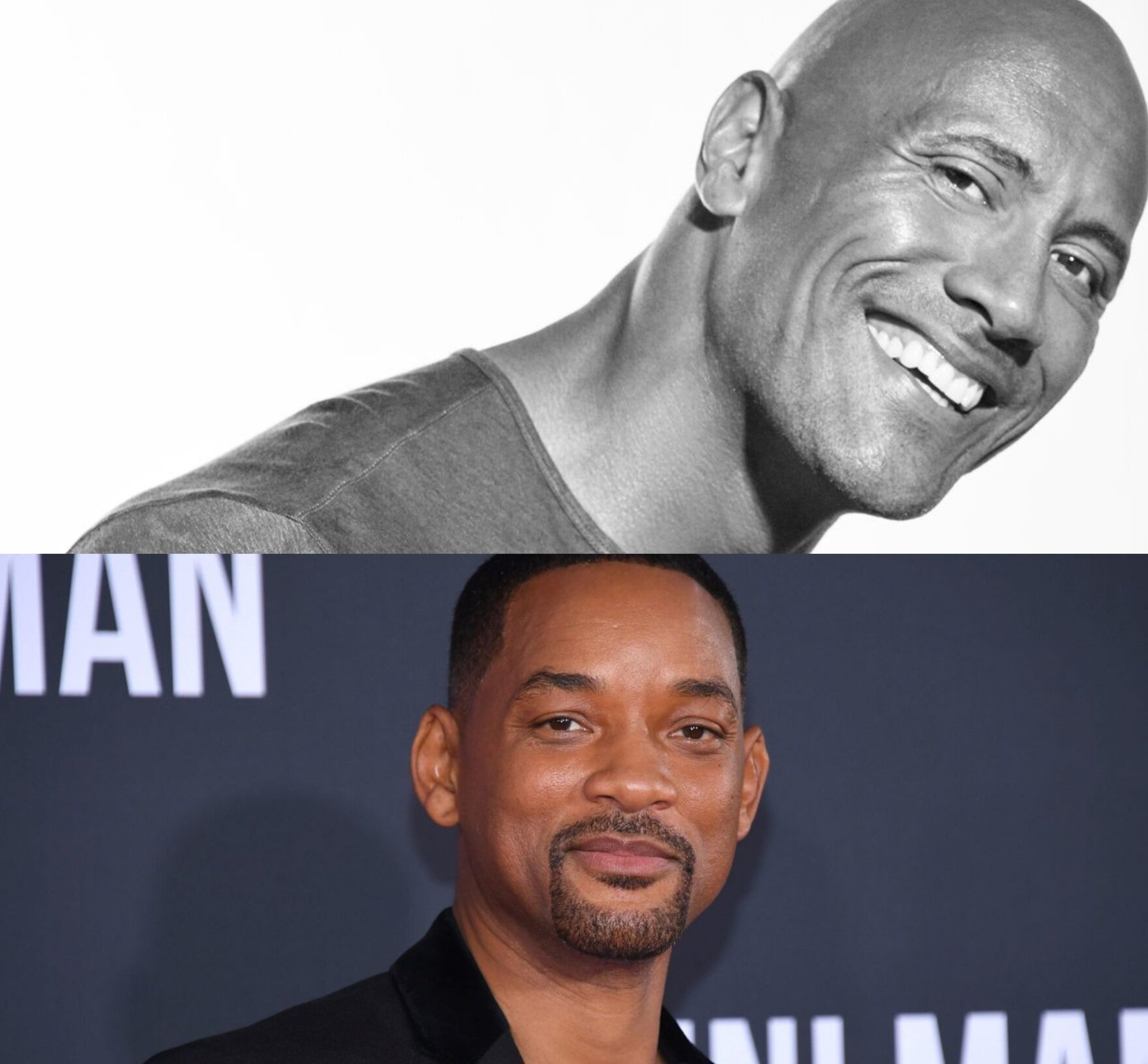

/I don't remember the first time I watched “Enter the Dragon”. I don't remember the first time I saw Bruce Lee or Jim Kelly either. These things exist in my mind as if they always existed, as if I had no choice over the amount of real estate they occupy on my head. I do however remember the feeling of first seeing each one, and in this particular case, in this particular month I want to celebrate that feeling about Jim Kelly, and more to the point Jim in Enter the Dragon, without reserve one of my favorite performances of all time. It is a role so dripped in the luminosity of blackness, and a certain type of black cool that would find its later iterations in a Denzel Washington, Laurence Fishburne, and Will Smith, (“I make this look good”) I don't think one can help but luxuriate on its ever present impact and legacy. What I find so impressive about that qualifier for me, is that I find Kelly’s actual acting technique ( if we can call to that) to be merely serviceable if not altogether underwhelming. I have a little giggle to myself as I say that, because it bolsters and corroborates his character “Williams” own words in the films text. When “Mr. Han” appraises his fighting style as “Unorthodox”, Williams dry retort is “but effective”. Touche, because in and out of text it serves as maybe the most potent example I can recall of the amendatory, sanctifying power of being the coolest m*****f***er on the planet.

Kelly cut an incredibly good looking figure. His body type was very similar to Bruce Lee’s, nearly lanky, but athletic. Detailedly chiseled, with a perfectly rotund afro as a cap that vice gripped a gaunt face. Thick eyebrows over soft eyes, cheekbones cut with a protractor, held in their parenthetical space an effervescent smile. Kelly was to say the least easy on the eyes, but interestingly enough due in part to what he lacked as an actor, and in this case what he possessed as an actor - those looks became an afterthought. Kelly's brilliance in this film isn't just relegated to one or two canonical scenes. The quality of his presence, the silk-laden assurity of his own cool is present from the opening credits. As they flash we get various vignettes of Kelly in various actions or non action. Kelly just standing as a low angle shot captures his essence upon arrival in Hong Kong. Kelly breezily crossing the street, or sitting in a boat, are all opening shots across the bow as to what will become unavoidably apparent in short time. His flat, laconic line readings of lines like “Ghettos are the same all over the world..they stink”- end up giving the text an elegant sense of blue collar sagacity. The sounds that came from his mouth as he exhaled while fighting were not the iconic birdsongs of Bruce Lee, but something more gutteral and abrasive -“Oooh Oyyy!”. His attitude was meant to place him in that long history of cinematic black athletes who are meant to be too cocky for their own good, from Apollo Creed to Willie Beamon, but by way of Kelly’s own charms it ended up being what allowed Kelly to set himself apart in a film devoted to its megawatt star.

Time after time when the film seeks to relegate Kelly to a blowhard triviality, he makes himself instead an arresting presence. About a quarter of the way through the movie Williams and the others are sent a bevy of the islands sex workers (probably more like slaves as it is later revealed) as a gift from Han, the islands benefactor and the holder of the tournament Williams has entered. Williams instead of just choosing one ends up choosing three, and then replies that if he left anyone out that they should understand because “it's been a long day”. In the context of the film this is meant to be a pre-emptive foreshadow as to exactly the trait that gets Williams into trouble..his arrogance. Outside the context of the film it is a affirmation of the long-standing trope of the black man as especially virile, a fetishization of his supposed special sexual proclivity as a devourer, and a bit of a mongrel. Kelly's natural equanimity and agacerie, don't subvert, but they do undermine the intentions of the text - he's just having too much fun with it to take the label seriously, it glides off him like so much water off a raincoat. By any tangible metric John Saxon's Roper is meant to be the second to Bruce Lee's first; the rakish rogue with just enough sense to know his place. His is an interesting and still rather cool role in this inverse of hierarchal status on film and even still he would end up an afterthought to Jim Kelly’s entrancing Williams. The massive appeal of a black man who used his training to train others in his community in self-defense against all threats foreign and domestic, (something akin to Black Panthers) his willingness to fight and beat the brakes off of police, and Kelly's own majestic sense of self evident cool proved too much for poor Saxon and his agent (especially in the black community) who reportedly had their fates in the film switched due to Saxon's own rising star. Even with his expeditious demise, Williams - and Kelly by association cemented his legacy in that very death.

After all, it may have been Williams who was sentenced to death, but it was us the audience who received his last meal, in those last moments before Williams is unceremoniously killed off screen Kelly would leave us with a flurry of endlessly quotable all-time line readings and an underrated fight scene. I'd like to imagine that contemporarily theater-goers were a bit caught off guard by Williams untimely death, which was not announced in the ways in which many films tend to do. Williams was randomly called to Hans office and we generally understand what he’s going to be called up there for, but that it will result in his death is something I gather we know now, rather than that was immediately expected. Either way, upon arrival and discovery of what it is he's been called up for Williams is in no mood to be cooperative. It could be said subtextually that in his particular office and position Han resembled too closely to Williams the police, and considering that long-standing relationship and the black communities concrete position on snitching, Williams found Han to be an immediately offensive character. All that before we get to the fact that the setup to the actual question is Han casting aspersions on Williams fighting ability. This barrage of personal insults leads us in order to Kelly's barrage of celebrated ripostes. “Suddenly I'd like to leave your Island”. “Bull***t Mr Han Man! (the a vowel dragged into it's own pool of audacity to taste of it) and of course “Man, you come right out of a comic book!”. Each word of that sentence is given a beat, a rhythm, that propelled it into our collective memory accompanied by Kelly’s uber fashionable and languid mode of verbal transportation. Before any of those lines are delivered Kelly delivers the biggest punch, the unforgettable last laugh. Not the best line just the one that cements his legend; When Han proposes to offer a subliminal shot masked as concern -”We are all ready to win, just as we are born knowing only life. It is defeat that you must learn to prepare for.” - Williams can barely hold his excitement to reply quite rapidly -“I don't even waste my time with it”. The words are delivered almost in song, eyebrows tossed in the air like so much laundry just before he pauses to add -“When it comes, (his body sort of sashays reinforcing his swagger) I won't even notice”. Han himself, allows his head to glide back into his chair replete with curiosity, not just in the “why” of it, but in the “Where” - as in “where did we find this one?”. Kelly not finished by a longshot gives the most unexpected and borderline hilarious answer; his confidence is not based in his study, or his read of the situation, or in some wisdom about winning not being everything, but in his own belief in his good looks and his ability to look good doing anything! Here again we have a situation where the text is calling us into judgement of Williams. There aforementioned historical context here, a long-standing idea emanating from white society (who typically could not beat us in sport) that black athletes and to some extent athletes or fighters of color were far more concerned with showing off, than being skilled. Once again Kelly undermines the intent to eternal effect. Williams does die, and more importantly and legendarily his premonition was correct; he was too busy looking good, for any of us to be concerned with it. So good in fact he ascended beyond all logic into the annuls of cinematic iconography.

Carmen Jones: Freedom Road.

/Carmen Jones. Dorothy Dandridge. The two names even and into themselves cause a commotion in the fused atoms that mark my being. I consider the two women inseperable, inextricable from one another. Co-creators of one another, neither as we have come to know them would exist without the other. Based on a play by Georges Bizet and directed by the renowned Otto Preminger (Laura, The Man with the Golden Arm, Exodus) 1954’s “Carmen Jones” (Jones being added to the original play name adds a heap of politics I don't have the time to get into now) is an ambitious, captivating, sublimely charismatic musical. It was one of the few musicals to have escaped the prison I had created for them in my mind -a rarity for me indeed since I used to absolutely “all caps” abhor musicals. This one I fell for immediately, Bizet's music compositions, the lavish beauty of technicolor, black people proved all too rich an invitation for me to ignore. The set up was simple enough, the doomed love affair between a strong willed, dangerously alluring, dreamer of a woman, and a prudish, naive, possesive, but charming young man. The politics too are fascinating with its sexual conflict and contradictions, racial anomalies, and gendered politics. All played a distant second the size of north America to my first infatuation with this film, because the first, second, and third words about Carmen Jones for me began and ended with the incomparable Dorothy Dandridge, Dorothy Dandridge, and Dorothy Dandridge. I was irrevocably seduced from the moment I first saw her. It was one of my first introductions to the power of a woman beyond her visage. Dandridge was gorgeous of course, one of the most beautiful women to grace the screen, but there was something else, something stitched in the eternal, but tied to nothing. Something vibrant and vivid about her energy, something mean but loving, love that frees rather than restrains. Her love was to be earned and you would walk barefoot on glass to prove it. I don't know whether I've always liked freer women or whether Dorothy’s Carmen taught me to love them, but that walk, that skirt, that attitude, they spoke to me of someone to be reckoned with, of tempestuous seas with shores of sunken men drunken with the sweet death of her sirens call. She walks into a mess hall like it was erected in her name. A random man puts his hand on her to try and gain a bit of her time and she shakes him off with the playfulness of a nymph, and the fierce skill of a running back. She merely put her foot in a man's chest and it became one of cinemas greatest accomplishments, a sensual masterpiece of body and frame. The first, second, and third words about this film begin and end with the incomparable Dorothy Dandridge, Dorothy Dandridge, Dorothy Dandridge.

From her opening salvo she was like watching lightning strike from a just safe enough distance as to feel it's corruption of the earth, but not be hurt by it, but Carmen’s entrance into the movie is quite unceremonious. There is none of the pomp, style, or celluloid stop lights of a Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard) or the sexual eloquence of Ellen Berent-Harland (Gene Tierney in Leave Her to Heaven) certainly not the cinematic manipulation of time and space that is Rita Hayworth’s intro in “Gilda”. The camera makes no unique movement, the music barely fluctuates, there is no preemptive exposition to announce her arrival. Almost suddenly she appears in a doorway sashaying in rather nonchalantly, equal parts; allure, confidence, power, ferocity, and sass crash into the screen. I loved her instantly. The spectres of the Jada Pinkett’s, Victoria Dillards, Nicole Carson's had faded into a darkened room in my silver screen driven fantasies. I was much like those men in the mess hall, who had forgotten their prospective or respective wives and,or, girlfriends to revel in her cosmic impressions. That iconic pencil skirt, burst aflame in red and orange while singing of her divine curvature dancing and floating across the sea of damp greys and browns. That iconic pencil dress which complimented and engulfed the black void of her blouse (a recreation of Saul Bass’s opening credits) was her only extravagance. No, in this picture the allure of Carmen was almost solely the allure of Dandridge. She stood in geometric shapes, very thrifty, arms out at acute angles, but she moved far more expensively -hips thrusting air as arms gracefully brandished an unseen apron. Dandridge (Who was dubbed for the film as well as co-star Harry Belafonte) was an actress in the highest order. Every one of her emotions were tangibly gusty and veracious. She glided through them, one to the next with a God-given charm and mastery. “You're too little and too late” she playfully barks to one suitor, meaning every iota of it in her drifting eyes. “I hate to be cooped up!” She replies to Belafonte, a visceral darkness gradually flooding the cinema of her face like a curtain. These moods are driven by something far deeper than the simplified Madonna/Whore argument the story beckons which Dandridge and Preminger dismiss altogether. She is both, she is whatever the season calls for. She is hurt and she hurts back, maybe doubly so. She takes the lead and is lead to whatever her wits analyze as needed for the situation. Her wantonness is celebrated in Preminger's visuals and the film becomes sadder the more tied down she becomes. All three understand Carmen demands one thing above all else; freedom. She said she could not stand to be cooped up and Dandridge's eyes betrayed the depth of that need and the trauma behind it. It could be argued that Carmen instantly recognizes the precarious nature of her situation and devises to use her obvious allure to convince Belafonte not to take her to the prison she cannot abide. Could be said once that was fulfilled one way or another she moved on. But, she also came back, back for more of that edge. A living embodiment of one of Newton's Laws of Motion; Whenever one object exerts a force on another object, the second object exerts an equal and opposite on the first. Who is the first and the second between Carmen and Joe volley's back and forth. The rocky nature of the relationship, the supremely possessive nature of Joe would seem to an outsider to be destabilizing - a version of looking for trouble, and that isn't necessarily untrue, but Joe may also represent to her a stabling force. Someone willing to exert an equal and opposite force on her, a first for her. Whether he's simply an opportunity, or kismet, is unimportant because what is important is that Carmen nonetheless is hungry for him, nearly as much as her freedom, and Dandridge feeds that hunger with pluck and command. One expression, smile, thrust of her legs, silk laden word, tornado of body parts fight at a time. A once-in-a lifetime unbridled star- making turn that burns so brightly it sits even now in the firmament of Hollywood long after both their deaths.

And underrated aspect of Dandridge that flares out in colors as textured as the film itself was that she was also very, very cool. Not “Gone Girl”cool, I mean Steve McQueen in a 66’ Mustang cool. Keanu Reeves deliberate cadence cool. Denzel Washington’s walk cool. Any room she walked in demanded her attention; be it boxing gym or shabby apartment. She talked cool, “I didn't come here to take up with that punching bag”. She looked cool, a thousand different versions of the eye-roll, and a thousand different thousand yard stares- my favorite of which is her glaring out from over the top of her glass as everyone else pours into heavyweight champ “Husky” Miller. It's presence, it's charm, it's skill of astronomical weight. The role interestingly enough did not come express mail to her door. Director Preminger and company had seen her work in “Bright Road” ; a middling first look at both a great actor and what would become a well worn trope in film about persistent teachers and wayward students (especially black or Latino students) in the education system. That film said nothing of the skills and attributes Dandridge would so provocatively display in “Carmen Jones” and so in another flash of the cohabitative nature of these two spirits, she took matters into her own hands. She had to show Preminger on her own, and came back with a vision, at which began in earnest the spiritual journey of one of cinemas greatest bits of iconography ever. If you had never seen or heard of Dorothy Dandridge before, you would know she was a star seconds into this film. Whether her satin-sultry stare, or fog cutting glare, Dandridge embodies a full-figured depiction of womanhood, the desire for self love and determinism in a world where she was limited by both her blackness, and her gender. She embodies lust, and yearning, the feast and the famine, the wreckage after the storm, the rainbow above that. In a film full of stars she is undoubtedly the central force in ways that rival, and arguably pale Marilyn Monroe in “Some like it Hot”, Elizabeth Taylor in the extravagant production of “Cleopatra”, or later toJulia Roberts in “Pretty Woman”. It is a testament both to what was, and what could've been, in Dandridge’s career, Carmen's life, before boorish men and their own righteous and unimpeded desires fractured the mirror and broke the frame. In this way Carmen and Dorothy seemed fated to the same meteoric rise and tragic fall, illuminating and advocating for each other to an end, and to their end. Dandridge of course did not die there, she went on to work in a number of other films and various productions off camera, but her star was never as bright, never as loved on, as crystallized as it was in Carmen Jones. For all intensive purposes she too was left there in the void that the role and her handlers (including Preminger) left. Only fitting that Dandridge's celluloid ghost should haunt men, and women alike together, acting as an asomatous ladder for her spiritual successors like Diahann Carroll, Halle Berry, and Kerry Washington. Looming over, lording over the heavens still burst aflame in orange and red, a constellation unto themselves free from the confines of a cell literal or figurative.

True Romance: Fairy Tales for the Working Class.

/A random encounter that leads to a love supreme, romance, hard won by way of the fires of jealousy, chauvinist chivalry, violence, female rage, and bull**** -That’s the cut and dry of Tony Scott and Tarantino’s 1993 vivid fever dream of mayhem for love “True Romance”. A movie so nonsensical, it only makes sense when you understand that that is its intention. This is a modern fairytale. It’s a funny thing, even though the bulk of these stories, as we understand them, were written by men, they are most commonly associated with the feminine. But they have always been as much for men as they have been for women, if not more. Romantic tales of destiny, courage, righteousness, and of course “true love,” could be argued to be more male driven than female, and Tarantino’s script, Zimmer’s score, and Scott’s enchanting lighting and color palette only further serve to justify the conciet and further the grandiosity in their particular tale, which is counterbalanced by its pragmatic look at how two working class people who need each other make their own magic.

Written by Quentin Tarantino and Roger Avary, colored in by Tony Scott, “True Romance”’s best quality is its distinct disdain for reality. Very little about it feels “real”. From the kismet meet cute of its protagonists to the four-team standoff at the end, this is a movie extremely proud of its movieness and its fairytale-dom.

Alabama (a heart-stopping Patricia Arquette in both look and performance) is a sex worker paid to court Clarence (Christian Slater, about as unattractive as you can possibly make Christian Slater) a sexless ne’er do well who is happy to be one, but unhappy with the results. After all, this may be Tarantino’s closest avatar, the man who bored and annoyed poor Fiona Apple to tears would seem to have a lot in common with a character who goes on random diatribes to random women who didn’t ask in hopes that his esoteric, concrete opinions on Elvis and Sonny Chiba will cause them to fall in love. Tarantino seems to have some sense of self-awareness though, because at first sight we see how bad this all looks. The first woman turns Clarence down flatly, but sympathetically, and the film seems to have no spite for her. It’s about the realest thing the movie does, because from here the movie becomes a “mad love” folk story: dark, unravelling, and opulent.

Whereas usually the woman sees their love mangled, here it is a man who seems out on his one true partner, and through a bit of happenstance and the scheming(of others) he meets his paramour. After Alabama meets Clarence and accomplishes her goal of wooing him to bed by listening to him intently, she too falls under his love spell. The “Why?” is hard to ascertain, and unnecessary. This is not a romance or a romantic comedy; we don’t need to see what made the two fall in love with each other; it is taken for granted that they are pre-destined. Why did the prince immediately fall in love with Sleeping Beauty? Why does the Little Mermaid (Hans Christian Anderson) fall in love with her prince from a distance? In these stories love is an enchantment, a spell; it is instant; it needs no justification, nor any reason. These are two people in need of each other and they recognize it instantly with no artifice, and like most fairy tales and even legends, love is easily fallen into, but peace in it is hard gained.

The same goes for prosperity in America, a straight-faced look at the fact that delusion is vital to any person(s) belief in “making it” in America. The American dream is simply that. You must create your own mythos, slaying dragons, conquering several quests, sacrificing in order to obtain a happy ending, but also in reality - lying, cheating, and stealing. Two of these things' cross paths and swords, and so must our two protagonists – with all the mythical creatures of the underworld. Those creatures in a modern setting are not dragons, witches, and monsters, but pimps, gangsters, and the notion of celebrity. This Little Red Riding Hood with her newfound lover in tow instead of meeting one wolf meets an arsenal of wolves, each one at a different stop dressed up as different characters in her world, trying to consume them before they deliver a large suitcase full of cocaine to live their happy ending.

The dialogue isn’t concerned with realism, typical of Tarantino, it’s not very concerned with the way people really talk either. Almost every monster they encounter has Shakespearean monologues on deck before every action, like riddles as a rite of passage. A pure killer stops in his tracks when the woman he tries to kill tells him to “wait.” When she says you look ridiculous, he is compelled to look at himself, like Narcissus at the lake. One of our protagonists sees Elvis regularly; Christopher Walken is Sicilian. The film has a voice over for a reason. These are two people with big imaginations, telling the audience the story of how they fell in love at first sight. Two people who needed to have a big imagination because their realities were too grave to abide in. So they meet at the movies, and movies being our modern mythology, and folklore, they decide to make their life one where beauty and ugliness live side by side, much like the fairytales of old.

That relationship between beauty and its opposite makes up the entire ethos of the film, and as such is complimentary to its forbearers who always sat the horrific by the side of the enchanting. Serene settings, and well adorned beautiful people are placed next to lurid tableaus of violent, vicious creatures, and moral depravity. “True Romance” is no less a world for the racist, homophobic, mean spirited. It’s a cruel labyrinth of decadence, full of the most tragic characters you’ll ever find drenched in fuchsia and pastels.

Clarence, now madly in love with Alabama is willing to do anything for her. This is beauty. Hans Zimmer’s whimsical score for them further suggest as much. But upon hearing she has been shackled by one of those mythical creatures- a white pimp who acts black and plays himself far bigger than his role in society – Clarence is sickened; both by the idea of another man having a hold on Alabama, and his treatment of women in general. He decides this man needs to die. We see Chivalry, chauvinism, and romance caught in a whirling dance. After vanquishing Alabama’s captor, a whole different story is unlocked.

Another small similarity to Red Riding Hood appears as Dennis Hopper (Grandma) is eaten by a wolf who lies in wait for Clarence and Alabama. The poetry is he won’t give up his son, that love means more than his life despite their troubles. Knowingly on his proverbial death march, he becomes bathed in the heavenly light of redemption before being shot in the head and spit on; beauty, and ugliness, restoration, and desecration.

Alabama is a sex worker, and for the most part her chosen career path isn’t vilified by the movie, (although her purity is restored by her willingness to join in unholy matrimony with Clarence). Alabama’s style itself is a mixture of the hideous and the insanely beautiful. It’s meant to be tacky, but the daring choices and lack of tact make her pop. She is also childlike and naïve. In one of the few departures from the common tropes of a fairy tale she is also a fighter and a slayer of her own dragons. When put into a room with a wolf she can become equally feral. This serves as the only proof that “True Romance” is nonlinear and messy, not evidence that it isn’t a modern fairy tale.

For all of this tale’s warts and hideous faces, its elegance and beauty are found beneath the surface of its beastly appearance. Much like the climactic bullet opera at the end, it's a blood-soaked feathered sofa, both comfortable and grisly. A hodgepodge of borrowed ideas from tales of old that came together like Voltron to form one big gooey theme; “Ain’t love grand”.

The Tragedy of Sofia Falcone by Cristin Milioti.

/It starts with a “clang”. A vibrating crystal trumpet announcing the moment. It was built to perfection- in episode, and in season. There were many times that though I had a clue as to possibilities, I wondered out loud why in particular Sofia Falcone (Cristin Milioti) bared her proverbial teeth to Oswald Cobb seemingly in perpetuity. Clues were dropped, a big one being the mention and discussion of a past betrayal of Sofia by Oswald in last week's episode “Bliss”, but it would be this week's episode “Cent' Anni” that revealed the source of Sofia's constant agitation and underlying anger as it pertains to Oswald and her family. A flashback episode that brings us directly to the present in which a reckoning will be had and as a result one of this year's finest performances in television via Cristin Milioti. In just about 4 mins Milioti would capture the physical and mental exhaustion of a traumatic past and the gasoline drenched fury that lit up her calculated revenge. A revenge brought on by a tragedy.

It started with a clang, a vibrating, crystal clear statement of intent to disrupt, that followed more subtle announcements when she sat down and loudly scraped her chair against the floor to move it towards the table, or showed the food in her mouth to her niece as her Uncle Luca (the head of the Falcone family) is giving a speech. Milioti who had dealt in understatement and elusiveness much of the season, is now beginning to purposely shake the bottled up radiating suds of her ferocity without uncorking it, though she does loosen it just enough for some palpable seepage. Shaking: “Wow look at everyone, I believe the last time that we were all together was my “father's birthday 10 years ago”. Seepage: I'm sure you will remember that night (beat) I know I do”. Structuring this so that prior to this speech we are explicitly shown the horrifying Cliff notes of a harrowing chapter in Sofia's life that underscore the betrayal that leads us into the now of her pain is a brilliant choice. Though 15 to 20 minutes is simply an abbreviated version of her 10 years at Arkham (for nothing other than remotely hearing what her father had done and to what extent it mattered believing) the extent to which we do see what she endured is enough to allow our imaginations to run wild about what the rest of it might have looked like. The abrupt and sudden nature of Sofia's commitment in conjunction with Milioti’s physical depiction of the shock of it is enough to flip anyone's gut. It is followed by a brief depiction of just how torturous, distressing, and wounding it was to endure just those first six months with a thought that you would get a trial in which your innocence would be proven a only to find out that those who claimed to love you made sure that you wouldn't even receive that tiny bit of a reprieve. All this from Family…Family?? The initial interruption of Sofia's hope in Milioti's eyes (so rich with text and crest-fallen trauma) is deepened in its resonance by the blank canvas of acceptance that becomes her face once it registers fully that she has no one to help her, and worse still (besides her brother ) no one that will. From this point on an evolution begins, and that evolution is built on the foundation of what was set up by the writers and by Milioti’s transformation. Young Sofia seems ripe with hope and belief, or rather trust. It's not just in the hair and makeup, it's in her movements, which are so much more smoother, and less stunted, but also less assured. The intelligence is always there, but to this point Sofia leans in and into her family and especially to her father. Whether a dinner table scene (a recurring theme) with her father, or benched in a limo talking to her brother - the reticence in her body, mouth, and eyes to assert herself or question is clear. So that when we come back to the Falcone dinner meet in present day Milioti in spirit, in energy could be said to appear unrecognizable.

The “I Know I do” in the recollection is made that much stronger by the fact that when Milioti says the words you can feel her voice tremble with traumatic recall. It's a slight rumble, a bit stilted, powered though by will. Air trapped in her throat for so long it atrophied and stumbled on its way out to freedom. In an interview for Cosmopolitan magazine Milioti says “She's either in Arkham or she's with Oz, who she can't fully trust, so she's always on guard. Her one ally was her brother. And it's not really until the end of that episode that she can take a breath and relax. I definitely tried to track how that would affect the way someone would hold their body”- the work comes though loud and clear. Her audience though remains still, save for one member “Carla” whose tries to leave the table because the truth might get in the way of her comfort, which is par the course for the entire table of fiends who either played an explicit role or were complicit in Sofia’s committal to Arkham. “As you all know, I was stuffed in Arkham State Hospital for a decade”- you can see the words move from her gut to her throat like bile, her eyes flutter and well. Gestures act as exclamation points and underline emotional text. Her hand moves away from her body as she she says “I was stuffed”, her thumb and index come together and her hand slams down on air, gavel-like. The way she says “decade” exclaims the viciousness of the act and the depth of its effect. The accent becomes even more pronounced as it does in anger. Once again this does not seem to be unintentional, -after all in that very same interview for Cosmopolitan Milioti says they thought enough to have her accent be lost a little from her 10 years in Arkham where she spends so much time in isolation and away from her people - it stands to reason it would come back involuntarily in moments that reach back to that time before. The viscosity of “Stuffed” and “Decade” carries the bitterness, the rage, the words in front of and behind carry the hurt in a way only such an up close and personal betrayal would as they foreshadow what's to come.

“Convicted of murdering SEVEN women” The seven is enunciated in Milioti's mouth even before she says it, most indicatively by the way her tongue presses into right side of her cheek - choices that emphasize how important these women were to her, as well as her connection to them. “Summer Gleeson, “Taylor Montgomery, Yolanda Jones, Nancy Hoffman Susanna Weekly, Devri Blake, and Tricia Becker, their names are worth saying”. It's a great bit of writing that conveys a surprisingly profound bit of understanding from writer John McCutcheon about the nature of being silenced. The crime is not merely family betrayal, nor the murders, or the sacrifice of an “innocent”, it is also the forgetting, the covering, the silence that covered these voices, is the same that now covers the room. “Victims are so quickly forgotten” our stories are rarely told”. The camera pans to the right to two Falcone women who have an air of recognition to the statement. It could be said that it is most likely each of these women has been victimized in some way. The mob is no less a misogynistic enterprise than the America it was born in, and a key element in Sofia’s story is that though she suspected and knew what her father had done she was in fact willing to be a good soldier and join in the silencing, but there's no protection from someone who hates the idea of your very existence is the lesson she gleaned from her experience. Johnny Viti (the always brilliant Michael Kelly) the family underboss/general has had enough, and tries to interrupt and end it, Milioti shoots him a look that in and of itself could secure her an Emmy, followed by the word “Yes and Hmm?”. It is not only meant to remind him that she's talking, but of what she has on him. She then returns to her speech. “I've had a lot of time to reflect, and I have to say I was genuinely surprised by how many of you wrote letters telling the judge that I was mentally ill..like my mother”. There is a “how dare you?” element to the cadence of “Like my mother” that speaks to the connection to her mother, which then reiterates the sickness of the act. This is fantastic writing consistently meeting fantastic performance. The flashback acts in concert with Milioti as the bucket in her well of emotion, ever so slightly rises. She chokes up as she says the very words, and in combination what we've seen prior, to how she found her mother, one death, and finding out her own father is responsible another death, and then her being punished and punished and punished for it a third it exhausts the audience connection to this family in a similar fashion to the way it exhausts hers. The moment pulled the bucket in my well as well, after all (and of course in varying degrees) who doesn't understand familial betrayal and what it does to ones heart?

“I trusted you..I loved you”. The well bucket rises higher still. It is in this section that Sofia comes the closest to full-on crying as Milioti allows it to wash over her now dewey orb shaped eyes. Recalling her brother's fierce loyalty and their cruel apathy she continues; “And you know the REAL thorn in my side is that unlike the rest of you, I was innocent”. Again the accent comes in as thick as peanut butter, and again the emphasis placed in words betrays the specificity of her pain- which is the shock of finding out just how disposable you are even to people whose entire schtick is supposed to be “family”. That disposability, exposed by the cruelty that lies in the fact that the idea of family in this environment is all but a joke could be argued to be the point of this episode. The tragedy of Sofia, even as she lives in a class that allows her privileges over Oswald is not too far from the tragedy of Oswald who lives in a gender that allows him privileges over Sofia, and that tragedy is the tragedy of the discarded. The unwanted, the unloved, the disposable, and how they can find no solace even next to each other, whether Oswald to Victor, or Sofia to her family, or Oswald and Sofia to each other, or extending our further Batman to Gotham. It's a bitter existence that leads to bitter people, broken people, with wants desires and ambitions that are meant to fill the holes in their hearts. The power they seek is meant to be a protection from this, but ultimately it cannot and never will, and all it leads to is a hunger that ultimately swallows and spits out others who will do the same. Milioti’s work conveys her new found hunger, not just in this scene, but in the one prior when she in-part flirts with, admonishes, and scares her therapist Julian Rush (Theo Rossi) she almost seems as if she is ready to take a bite of him. Sofia's turn is not that of a pure innocent to a world destroyer, but it is that of a person who found out in the worst way their class, their status, was not a protection from the built-in expendability of their personhood. That their seat at the table in no way meant that they werent food and it is Milioti's performance that works in concert with the script to show exactly what that looks like, and furthermore what the transformation from one who is on the plate - to one who holds the fork looks like. Fitting then that this scene took place at the dinner table in a story of those swallowed and those eating, and in a scene where the actor Cristin Milioti clearly had her fill.

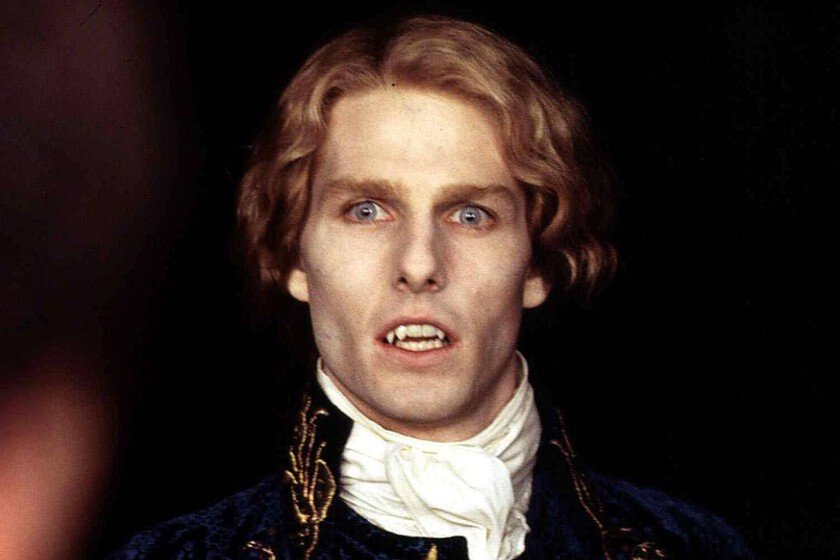

In Defense of Keanu Reeves in Bram Stoker's Dracula.

/“It's is the man himself, look, he's grown young!”. It's a line reading engraved in my memory owing to the severity of its anachronistic delivery by one Keanu Reeves, and is (I believe) a microcosmic example of the wide spread belief that Keanu Reeves was both horribly miscast and painfully bad in Francis Ford Coppola's classic adaptation of Bram Stoker's “Dracula”. While I too patroned this church for some time, the more viewings I had (and I've watched this movie and unnamable amount of times) the more I started to find that Keanu Reeves performance is an integral ingredient to the recipe. Francis Ford Coppola's “Bram Stoker's Dracula” is a lush colored fever dream come to life, toggling between one world (the old ) and another, (the new) magic, and science, both in its consistent anachronistic juxtapositions, and in it and the book’s anxieties around sex, gender, and class. Keanu’s performance mirrors, refracts, embodies, and reinforces these things and in its willingness to repel lies it's magic.

When you watch “Bram Strokers Dracula” there's a underbed of understanding that you are looking back, and the looking back implies a future- which implies a modernity, the lens of which guides it's point of view and it's expressions about sex, gender, and class. It's declarations and prescience about the creeping insurgence of industrialization and the modernization of technology, ideas concerning things like a burgeoning feminists awakening and cinema birthing itself have those conversations from the point of view of someone living in the “now” not the “then”. It does this even while clearly doing an outstanding job of worldbuilding the “then”. Its expressions of the old are in that worldbuilding, it's expressions of the new (though present in some of that world building as well) are most readily present in its casting which went away from our old understanding of who and what these characters look like and what they represent. Keanu Reeves’s prepubescent face, off-kilter style of acting, provided a contextual contrast between old and the modern that aided the movies themes. He, Wynona, and Billy Campbell, represented not only America, (the younger symbol of empire and conquest) but the more modern class of acting against the olden background and the foreground of classically trained brits like Oldman and Hopkins. It enhances the sense of Jonathan Harker as an outsider, reinforced his foreignness. There might have been better actors, but there was no one who was better suited to inherently reflect the themes of innocence tainted as well as the sense of the awkward expressed in the film. After all this is what Keanu Reeves built his career up to and after that point of his career. It's not hard to look at Keanu’s career and note the connected thread of work around the expression of mental agitation, anxiety, and alienation with performed identity and their place in the world. The River's Edge”, “Bill and Ted's excellent Adventure”, “Point Break”, “My Own Private Idaho”. Each of these are men in search of something, anxious about a sense of oppression and obstruction from who they really can be. They can't quite articulate it, and are alienated by that inability. On most occasions these men find a partner (usually a man) whom they hope to find answers from and do but also find more questions. “Bodi”, “Morpheus”, “John Milton”, “Count Dracula”.

One definitive through-line in Reeves’s career has been that of the male ingenue. He’s believably unsophisticated, (though he comes off the opposite when he speaks as an actor and person) and usually plays some cousin of virtuous and/or innocent under threat, many times from the person whose spell he’s fallen under, and of course he is beautiful. Like the classic Hollywood sexpots that came before him -the Monroes, Taylor's, and Garbos,- he reeks of sex and sexuality. Its an attribute that engages in an alluring dance with their innocence, one that only furthers our desire for them. We also wish to see them protected, which clashes with their actual lives which they guard and protect fiercely, only adding fuel to the fire of the allure. Ingenues on film historically need guidance, someone to be of aid and service to them, but also protect them. This too is a through-line throughout Reeves’s career. Sometimes these people can also be the very ones meant to harm them. In “Dangerous Liaisons” it’s Glenn Close who patronizes the young virtuous Keanu, who is ignorant of all the ways in which she toys with him- even in the end he staunchly defends her. In Kathryn Bigelow’s “Point Break” it’s Patrick Swayze’s “Bodhi”, whom he ultimately can't even bring in, because to do so would be to end that relationship, and worse still, destroy everything he loves about the man. If the quality of naivety, of the ingenue, the eager-to-please doesn't embody in any major way the qualities you would associate with Jonathan Harker, then you’ll find exception with the fact that he doesn't conquer any aspect of Victorian-era British identity in that role, to say nothing of the accent, but if you, like I think this is a spot-on summation of Jonathan Harker, then Keanu’s casting becomes much clearer.

Keanu is as close to an ingenue as it comes for a male movie star. Even more though than Keanu's virtuous candor, and ready-made innocence, his mastery over his body is another vital ingredient to making his performances work. One of the most glaring and consistent attributes of Coppola’s adaptation of Bram Stoker's novel is its obsession with movement; Coppola twists it, and gnarls it, slows it and speeds it up. Dracula's shadow, the strange carriage rider and the eerie way he reaches out for Jonathan are related to the unnerving quality of the movement itself. The opening sequence features the use of puppets for its opening battle, their stunted and stilted movement, versus the interpretive dance-like quality of “Lucy”s (played exquisitely by Sadie Frost) movements also bears this out. Whether walking through the garden in the night possessed by Dracula’s murderous hymn, or in sexual ecstasy with a wolf, or climbing back into her casket, movement is the life blood of Coppola’s film. This makes Keanu’s casting a bonafide compliment considering what is arguably his career defining trait. He's become one of America's greatest action heroes precisely because he understands his body on camera and moves with incredible agility and intensely alluring grace. This all comes to bear in Coppola's film. The most vivid example is Jonathan's seduction at the hands of Dracula’s brides. The scene begins innocently enough with Harker exploring the part of the castle the Count specifically told him to avoid. He wonders around with that “Reevesian” otherworldly awe that undergirds even the plainest of his line deliveries (“Whoa”) as he wrestles with things he sees but cannot understand because he is a rational man, both in matters of earth, and as we see, of sex. His curiosity eventually leads him through to a bed, beckoned by the possibilities of sexually charged mewing of Mina’s voice (he has so far denied) in the darkness. Keanu had even by this time long been accused of being wooden or stiff, it was then as it is now an impossibly lazy and reductive statement that made its bed in the pseudo-“surfs up” tonality of his line readings and never bothered to survey the house. Everything Reeves does is with direct intention and understanding; he sits down on the bed, stiffly but in anticipation. When the first bride arrives and it is clear he is under their spell, Keanu's writhing and moaning suggest where Harker is at with his sexuality, it is forced and restrained, also freeing. He opens his legs as if struggling to do so, sits up rapidly and nearly yells in sexual bliss. The sound both repels and attracts us, a climax for Harker’s own arc towards depravity and sexual freedom. When his trance and ecstasy is abruptly interrupted by Dracula's appearance, and he is forced to watch as the brides are offered the consolation meal of a young child the horror on his face could be ascribed to not only what he is watching but what he has been party to, and what in essence he fears he may become. The build up to- and the subsequently the resplendent look of horror in his face, is one of the great facial expressions in cinema empowered by how he uses almost every corner of his visage, and the logic by which it is viewed as bad acting escapes me to this very day. The trauma of the event, the euphoria amid acts he did not consent to changes Harker, and that change is apparent in Keanu's performance. Afterwards, he is less stiff, more dour; in grief, but also surer of himself. The Harker that Reeves shows us at the beginning of the film was a fumbler of words, an awkward man in front of those whose respect he desires. The Jonathan we see at the end now leads men; he knows of his own words and place in the world. He is present and less fashionable with the presentation of manhood common at the time, he’s Keanu. Harker’s newfound confidence is never more present than in his first conversation with Anthony Hopkins’s Van Helsing. There’s a sincerity in his face, his breath, the downcast eyes when he speaks his fear, a testament to his vulnerability, and where he was before his sexual awakening which was also traumatic. The confidence we hear in his delivery of "I know where the bastard sleeps" the loss of it in "I brought him there". Forget how his accent sounds; that’s little more than a distraction. Watch his face and body, and you’ll see the essence of Keanu.

Keanu’s face and especially his body (as per usual) is his greatest weapon in the film. His child-like sense of wonder and curiosity a close second. To watch him is to watch the transformation of Harker as much as it is to watch the transformation of Dracula and the world that has left him behind. The almost the universal disdain for this particular role is trapped in a universal understanding of the expectations of the genre, and of this particular story, and of our ideas around British-ness. It is rooted in the exaggerative power given to the conquering of an accent which would make for a whole different essay. The hyperbolic consternation with Reeves casting and the performance is as incurious and banal to me as those who seek to have their favorite comic book characters or cartoon characters be a one for one with the actors who play them. It shows a blatant disregard for imagination, and worse still for the considerable skills that Keanu brings to any role- despite what effect his well known inflection may or may not have on the role. While I wouldn't venture as far as to call this one of Keanu's best roles, I believe it is most certainly one of his most interesting, as a casting based more in spiritual recreation, rather than the spot on avatar of the Jonathan Harker we've seen in just about every other representation or adaptation of the book. The role is best looked at as yet another tool and anachronistic symbol of Coppola’s contradicting and competing themes to which Reeves stood out as the most realized of all.

Shelley Duvall : Stardust and Invitation

/She was very easy to let into your home, that is the first thing I would say about Shelley Duvall. Waifish, tall, spindly, with a voice that perpetually shivered in a broken falsetto, and two perfect camera apertures in the middle of her face - she carried with her the presence of something eternal, and yet fragile enough that if you were to touch her she might disappear into the fog of your awakened mind. To a young child like me very few things were safer, more magical, more inviting. On-screen Duvall didn't come to me through her considerable body of work in the seventies for directorial institutions like Robert Altman, Woody Allen, or Stanley Kubrick, but by way of an anthology TV series for children called simply; “Faerie Tale Theater”. When we didn't have cable we rented the collection from the library, and we watched religiously as Shelley delivered us kids our version of the Twilight Zone via the Brothers Grimm, Hans Christian Andersen, or Charles Perrault. Shelley didn't just seem a host to me, she seemed like she herself possessed the magic of these worlds in her lithe features, most especially in those perfectly round large spheres that somehow seated themselves so symmetrically in her face. Week after week she introduced a new brilliantly acted take on our favorite fairytales with the warmth of a fresh baked pie on window sill. Setting us up to cross into a new dimension where these tales felt as mystical, extraordinary, and funny as they did on page. To this day it is one of my most favored and cherished memories in my childhood, and she is as synonymous, as connected to spirit of that show as Rod Serling was to the Twilight Zone. Much like Serling what made Duvall so appealing to me was that she gave promise to the idea that our best selves lied not and what we could already see, but what was behind that, and what our imaginations could conjure. As an actor she was as singular as her “Nashville” co-star Jeff Goldblum, or Linda Hunt, or Harry Dean Stanton, but she was also a much larger, bigger, than them -a genuine movie star with the strongest sensibilities of an character actor. That character was loving, curious, child-like, and grown. There was no actor before or after her that embodied the dream, the fantasy, the fable, quite like she did. She was an actor that provoked the imagination by simply existing.

Though Faerie Tale Theater was my introduction to Duvall, it was not where I finished. Cable TV would soon introduce me to her roles in Robert Altman's oddity “Popeye” and then to her role in Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining”. Though both were a lot more grown up material than Faerie Tale, her very magical, mystical, and ethereal quality remained. She was the perfect gateway between Robin Williams’s animated chaos, and Altman's demure humanity. If you needed a ferryman to get you from one sensibility to the other you could do no better than Duvall. What Roger Ebert accurately pinpointed as a “dignity” is directly in alignment with Altman’s stylings. It keeps the otherworldliness of what lived on the pages of comic strips and served it empathy, flesh, and something rooted in the earth of our imagination. Every neck turn, every confident inflection of an out of tune tune in “He needs me”, every incongruous movement lent further credit to the possibility that these places were real, that “Popeye” and “Bluto” were real men, that “Sweethaven” was a real place. Her abilities were such that ink became 3-dimensional skin and bone right before your eyes.

In Stanley Kubrick’s seminal take on Stephen King's horror classic “The Shining” his vision redressed much of what was in King’s text. Kubrick aimed for something much more subversive and elliptical, rather than the plainly paranormal. The supernatural may exist in Kubrick’s version, but so too is the very real frights of abuse and colonization. As “Wendy Torrance” Duvall masterfully carried both as realities in her petrified melancholia and stressed out cigarettes. Duvall; one of my favorite cigarette actors of her generation,(right along with Dean Stockwell and Robert DeNiro) with every puff, with every tension filled exhale, or the angularity of her hold on the cigarette and it's magical ash gave raison d’etre to our imaginations as to what horrors lay behind this manicured perfection. It is Duvall who is haunted long before we find the horrors of the fabled Overlook hotel. Every word, every look feels chosen to decide the right intonation as to not piss off the ghoul in the car with her. Her movements, are repressed, her eyes devoid of that magic that made her so beloved, and it is only when all hell breaks loose that she begins to reveal again her supernatural soul. As her eyes widen, her screams unlock the cell of her prison door and out comes a woman driven by her will to survive. The magic is there again and through her reflective and scaling fight or flight responses; whether to her son's increasingly strange behavior, or the off putting eeriness of the house, or Jack’s bizarre typed refrain, we see the incarnate evil that has been unleashed be it human or other. The weight of both worlds seen and unseen stiffen her arms as she tries to swing a bat at her husband. Sit on her shoulders as she falls to her knees after locking him in a freezer. Without her otherworldly presence that doorway remains shut, and “The Shining” is merely one thing based in reality, or another based on the supernatural, rather then both operating simultaneously.

The magic of Shelley Duvall was that she was completely her own thing, and thus could be anything. Her style of acting in concert with her definitive looks made her appear both as something firmly from here and from somewhere else. She could've been “The Woman that Fell to Earth, or “Star Woman” or “Gandalf” or “Galadriel” by sheer quality of her alien like aura. Even as a “Rolling Stone” reporter in Woody Allen’s “Annie Hall” she seemed like something you'd find in a curio shop on a crisp fall day in a town in the nowhere. In a way, its as if she was discovered that way. Born and raised in Fort Worth, Texas in 1949 she was in her own house a bit of a curiosity. The oldest of four, she was nicknamed “manic mouse”. Eccentricity and energy already welded to her like sheet metal. She was discovered by Robert Altman in 1970, her essence already by then so palpable that she has won over just about everyone she ran into. She was genuine stardust. A reminder of what the best of us could achieve if only we let go of the safety of normalcy. She had no peers, no doppelgangers, no successors, we got one of her, and that was more than enough magic to make this world that much more bearable and believable as its own tale of sorts. A consummate storyteller in the form of an actor whose entire career was inviting us into our own imagination by letting her in.

Acting and What is Left Behind.

/When I was young somewhere under ten and above five (I don't quite recall) I was in our church’s Nativity Play. I was set to be one of the three wise men, and I don't remember much before or after, just that when I arrived on stage I could not see the north star, but rather a sea of penetrative eyes staring at me, waiting on me to “become” and I was afraid. Afraid like I never remember being afraid before. I truly don't remember much after, save for a kind of feeling I was in the middle of a tornado of hubbub when I was hauled off behind the stage with people offering all kinds of sentiments to make me feel better as I cried my eyes out. I never really looked to the stage again or thought about acting (outside of the terms of just immensely enjoying spectatorship) until almost 30 years later. I was always shy, and in many ways I still am. I preferred the sprawling open worlds of my imagination to the itchy, hot, volatile, oppressive, and restrictive real world that I live(d) in. Even today, in the world inside my head I am an avid performer. I love being other people, stepping into the mines of the mind of another person felt like Professor X entering “Cerebro” in X-Men. In the real world I was far too afraid of people's rejection. I learned very early on that there were different planes of existence one could choose to operate on and to think about the world in that way. Finding a way to conjoin the two is the journey I still am on. Acting, and the act of it is about the two different planes, the one that lies in the subjective reality -that to some extent has been chosen for us by things like socialization and the limits of our senses, and the objective reality on the other side of our senses, and in that sense on the other side of our “sense”. Once you enter into that plane which is acting, the better you are able to let go of everything that you were told on that other plane behind you the better, the more effective, the more profound you're acting is. In essence you enter the nonsensical, the surreal, while also living in the real.

That “truth” we speak of consistently as actors in the study of the craft is about this very idea. The thing about this “truth” is it is not a truth in the sense that it factually or realistically exists on this plane all the time. It's a truth in the sense that it is something that we all strive towards, or something that we deeply want in the most deepest reaches of our spirit. Philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty wrote “Our body is the general medium for having a world”. Rene Descartes be damned, the body, our bodies, simultaneously experience itself and the outside, itself and the other. The pursuit of acting and the “act” of acting is the only art so directly a portrait of this philosophy, because making plays or movies are the only arts dedicated to this philosophy. At their very core the play, or the movie, is a direct acknowledgment of the fact that almost everything - from our God to our names, came into being and import to us directly from the void of our consciousness or our minds. Everything on a stage, or on a set, is a recreation of the creation of our world. Somebody's vision realized by a number of various craftsman created a reality from the cloth of their imagination. To make sense of this compromise by interacting consciously with this “truth”, is the ideological ideal that we get to watch or “be” on stage or screen. When we are praising a performance, what we are praising is not simply craft, skill, and technique on display, but that ideological ideal of an aspect of ourselves we would love to be free enough to be. In every single movie ever made there are people doing things that people on an everyday basis never do, that for many of us are physically impossible to do. Some of those things are righteous, some are not. A great deal are necessary to a just world, and a great many are arbitrary and set up by those who are freer than the rest of us, though not free enough to not hate the idea and the possibility of someone being freer. Again, a recreation of our world in a world where we are in recognition of both real and not real.

German Expressionist painter Max Beckmann once said “What I want to show in my work is the idea which hides behind so-called reality. I am seeking for the bridge which leads from the visible to the invisible.” That exact bridge should be the similar goal of actors in many respects and the “crossing” something the critic should be more interested in. Fortunately, in the world of critics there seems to be a rising tide toward exactly this, recognized in praise for Jason Momoa in “Fast and Furious X”, Mia Goth in “Pearl”, or Ewan Macgregor in “Pinocchio”. Still there is far too much of a dependency on the attributes most readily associated with realism in young actors, critics, and casual observers. If I may be exhaustive for a moment, the bulk of the last several best actor Oscar winners being real life people is an example of this dependency. Ben Affleck in “The Last Duel”, Jared Leto in “House of Gucci” (actually one of his best performances) being up for “Razzies” are in some ways examples of this. Bradley Cooper’s effort in “Maestro” is an example of this. The misunderstanding of “The Method” is an example of this. The preciousness around subtlety is an example of this, the general disdain for fantasy as a genre is an example of this. “Hamming”, “Camp”, “Over-the-top” the in-and-out of favor nature of the connotation associated with these attributes, the misunderstandings, are in some respects an example of this. Why should that be? When the fantastical is such an inextricable aspect of the medium? What scares us and draws us to movies and these characters is that they are so real and yet so non-real. The “magic” of the movies could not/cannot exist without the cohabitation of these two aspects. These are real people exhibiting real emotions in completely made up circumstances, many times in completely made up places, but the make-believe of it all is more than just the material-physical reality, but that they exhibit behavior and feelings so freely in a world so free of the horde of woes that are visited upon each and every one of us several times a day everyday. In “Lethal Weapon” Danny Glover's Roger Murtaugh who at best could be pulling down 40k a year is free enough not to have to worry too much about the fact that he voluntarily drove his own car through his own living room, nevermind the damage he and Riggs (Mel Gibson) inflict on the city, nevermind the bills they have to pay on a house that seemed just a little less sizable than the “Home Alone” house. He is also free of any worries a black man living in that neighborhood might have in the 80’s and 90’s. In all of “real” television history have we ever seen anything like Peter Finch's monologue as “Howard Beale” in Network? Just about any one chase scene in an action movie would be the news for the year, and live on in infamy for years after. Hell, the OJ Bronco ride was boring as hell and lives on to this day. It is because of these existing realities and the consequences in our “real” world that most of us have never seen these things happen around us. This is a lesson to no one, but it is something that I believe important enough to remain vigilant about being cognizant of in the evaluation of both performance and in many cases movies as a whole.

We admire performance because it finds that particular “truth” of things many of us know and feel but are too afraid to say and do ourselves. That the aforementioned Mr. Finch in Sidney Lumet’s seminal piece did so with such reckless abandon, ferocity, and courage in the act, (both in the context of the play, and in the context of the “act” of playing) is the source code of our infatuation. We commend the “I'm not gonna do what you all think I'm gonna do, which is just FLIP OUT!” freedom of Jerry Maguire, but we're also at the same time admiring and applauding the freedom of the actor Tom Cruise to find that “self” that we are all so afraid of -so realistically and without any sort of resistance or abandon. The “flip out” is exactly what we want most. It’s release, it's cathartic nature is what we've been waiting for since he sat down at the table and watched the smug histrionics of Jay Mohr as he gaily tells Jerry he's fired. That “truth” is not so much tied to our reality as it is the truth of our collective fantasy, and the movie unconsciously and consciously acknowledges it, as does that very line in the script. You get far enough down the road considering the limitations of our senses and you understand we don't have the slightest conception of “truth” and in that sense every one of us is participating in some form of faith based upon those very limitations. This is the spiritual nature of the “act” of acting. Spirituality can be defined as a religious process of reformation which aims to recover the “original shape of man”. So while this may not be a religion per se, it is a process of reformation. The thing we see when we see somebody able to come back to something resembling our original shape, is something that maybe only existed (and never even fully then) when we were children. That these people (actors) are still able to hold onto that, to find that, and shed the baggage of this plane to enter into one that is such an idyllic but frightful place to live in…There, in that place is the “god” of acting. Proof that the nearest thing we have to utopia is the stage, the imagination of writers, vision of directors, the performance of actors and the movies. Real bodies existing on a screen within real settings surrounded by matter that we understand is part of the connective tissue that is realism. In performance it is reinforced through the tools we have available from whole disciplines and technique’s such as the “Method” or “Meisner technique” to the “magic if” and “emotional recall”, but it is all of it activated by imagination.