I don't understand the world we live in. One minute it's in awe and devastating recognition of acting giants like Denzel and Robert Deniro and the committed talents of someone like a Jim Carrey and the next it's telling me that Chris Evans is Robert De Niro and that Channing Tatum is a brilliant comedic talent.

King Richard Doesn't Trust Us.

/Movie stars can present a very interesting conundrum. Their special ability to bring presence in a film that materializes in such a very specific, magnetic, and near magical way can not only draw people to your film on their behalf, but in the right light and casting they can elevate and bring transcendence to the work..OR they can capsize a film, disallow you from being able to suspended belief, or over emphasize the lesser aspects of your script. While I don’t think Will Smith as Richard Williams capsizes Reinaldo Marcus Green's “King Richard”, (In many ways the script is in alliance with this aspect of Will ) he is definitely the latter of these two possibilities rather than the former. There is a sense of the same artifice that has made him one of the world’s most likeable actors here on display in this Oscar bait as Richard Williams the father and coach of two of America's most brilliant, successful, and talented athletes ever. There has always been a dichotomy to Will's good-nature, it makes him loveable but keeps us at a distance, and it allows us to trust him when he clearly doesn't ’t trust us with his true vulnerability on the line. So he gives just enough to satisfy but never enough to hurt him and thusly we are rarely hurt by him on screen in that oh so good way that great actors can on screen. That lack of trust seeps it’s way into the story King Richard seems to want to tell, and though it’s hard to tell how much of it is Will and how much is the movie, its clear neither are fully on board with trusting us to hear and see the very worst right along with the very best of Richard.

Watching the film it's pretty clear what King Richard wants to say about Richard Williams. The movie wants to present a flawed man who had a resourceful and willful desire to see his daughters reach places that he himself and others he saw around him never saw. You get the sense that the film would like to present a balance of Richard's ego and harmful self aggrandizing versus the social economic inhibitors and buffers black people face just trying to be anything in an unjust world. In a nuanced way this this film would have been a film I would have loved to death, something of an ode to black fathers and a critique, and in fits and spurts you get pieces of that type of film. The beginning of the film features a sort of montage of Richard's various meetings with various white Tennis coaches that turn him down in various white ways. The scenes properly demonstrate these buffers be they economic or racial, and they play well against Richard's insightful, driven, but also overbearing personality. Later on in the film when there is an argument between Richard and his wife ( played quite wonderfully by Aunjanue Ellis ) about his stubbornness and his unilateral decision making , we really get a taste of where and when his will meets walls that make him a very tough man to live with and morbidly insensitive, but these moments also end up showing the film's scriptural weaknesses every bit as much as they show its strengths, especially as it pertains to Will Smith. Maybe the greatest moment of conflict in the movie comes a full hour and 39 minutes into the film, which is problematic in and of itself but pushing that to the side- we see Richard get into a second confrontation with his wife over yet another unilateral decision made by Richard over whether or not his daughter will attend a tournament. Now it’s important to state that the first time he does this Richard is warned by his wife that he can never again make another decision like this without first consulting her and without really listening to what it is his girls actually want or there will be consequences….and yet he does it again and script wise, there is no real consequence or push back that comes from this, simply more talking. This is in fact realistic and it happens in many marriages and close knit relationships, but this doesn't come in a way that allows or conjures examination about Brandi and her position, how trapped she might feel, or maybe even erased by a man who continues to be wilfully obtuse about his own need for martyrdom and to be the singular figure and role player in these girls lives. Will Smith's compounds this issue because he himself has built such a career off being likable he simply does not pull off in any meaningful way these traits beyond the most basic ask of the writing. I don't even think it's that hes not trying, it’s just that the idea of being able to go to that place where you yourself become ugly to the audience or nasty, mean, vile , or any of the sort is foreign to him.. he doesn't understand the concept. Don't let the words I used fool you into believing that I think that Richard needed to be vile or necessarily nasty I'm just bringing them up as varying possibilities for that I know that Will can't do. For this film I think mean spirited, rude, obnoxious, cold, thoughtless, and condescending, as it pertains to the script depiction of Richard come to mind, but only through the piecing together of exposition and context. Will himself doesn’t give himself over to very much of this. For context and comparison let's take a look at another scene which I think exemplifies even the slightest level of that want or ability to make oneself appear unlikable, I’ll use this scene from Michael Mann's “Heat”. Where DeNiro first meets Amy Brenneman…

What Deniro captures here is a steadfast myopic dedication to one's own protection, Which he is willing to embody because of his philosophical approach as an actor, and subsequently the fact that DeNiro has spent the greater part of his career playing characters that float between the dynamic of being extremely charismatic and extremely deviant and or unlikable. Will Smith too is playing a character dedicated to a steadfast and myopic protection, except for this time it is not only himself but it is also for his daughters and their career. The difference is neither the story, nor the the camera, nor Will Smith are willing to dive all the way into that space in the way that DeNiro and Mann are willing to. Will Smith has made a career of careful curation and meticulous formulation. He has trained every part of him to respond to things in a way that most effectively increases his likeabilty and thus his box office. There is a scene that takes place just before the major conflict scene between Richard and his wife, Where we see that particular argument is initiated by an original conflict between Richard and the girl's new coach Rick Macci played by Jon Bernthal. Richard announces that he is taking the girls out of practice and junior tournament competition, and Director Reinaldo Marcus Green never let’s the camera sit on Will's face for any length of time but it is especially ignored or distanced when he has something nasty or mean-spirited to say. Green shoots from the side when Will all but calls Jenifer Capriati a crackhead. When Will's Richard goes on about how it’s his plan that has guided all this to Macci asserting his dominance -Green goes over the shoulder, and when Richard becomes sarcastic and demeaning about his wife’s role in crafting their Daughters skillset , again he is slightly over Wills shoulder. Now obviously you want to capture the other perosn’s reaction, or in the case of the latter maintain the POV of the character who is speaking (Ellis), but there are ways to do this without losing the impact of what Will is doing that have alot to do with changing some poor blocking for the needs of the scene. Even still the choice is understandable as when the camera is focused on Will he is unable to deliver the proper tonality in his face needed for the emotion within the context of these scenes. When his wife brings up Richard's past its one very clear example of a certain hollowness in Will's skillset, and in he and the movies will to trust us. In any space or context dredging up this past would be something that would probably set someone off. Not necessarily in any way that demonstrates or alludes to violence but just something that would deeply knock them off balance, but Will is always on balance and there is none of what should be registering on his face there even though his words and the things he retorts back to his wife are clearly indicative of the kind of underlying hurt and anger that should appear on Wills face. What this does is take away the full power, impact, and resonance of this particular scene unless you are paying sole attention to the words. So that a scene that should have the impact of Denzel Washington and Viola Davis in Fences where a husband and a wife are clearly confronting past sins and hurt that they have not been communicative to each other about - Instead feels more like a it's a simple disagreement about the direction in which to drive. ..

Extra marital affairs in the case of “Fences” and abandoned children in the case of “King Richard” are not light work, or subjects, these are the kinds of discussions and retorts that would most certainly inspire great disappointment, anger, frustration, hurt and more. Those emotions then as a consequence would inspire and create power through impact - that is what we saw out of the seminal and now classic Denzel/Viola scene in “Fences”. I don't know that anyone believes that fences is one of the greatest films of this era or even that there are that many people who love it in its entirety, but people KNOW that scene and its impact has carried well beyond maybe even the popularity of that film. Where was that scene here? All the trials, from within and without the family, and yet no scene really carries, and with so much time spent with the camera on Will, that’s an indictment. Will is a talented actor who like Tom Cruise has a sitting veneer that when explored could produce fascinating results, ( See Interview, Collateral, Born on the Fourth, Magnolia, Eyes Wide and the beginning of Edge of Tomorrow ) but while Cruise has explored this quite a few times in his filmography, Will hasn’t really explored it since “Six Degreees of Separation” and it shows here because all this belies what is most important to the storytellers involved, especially it's actor. Will Smith as a celebrity now spends abundant amount of times acting like a social media influencer. He scurries about in circles telling the same stories through different funnels about moving beyond obstacles and dismissing real impediments as trifles that can be resolved by nothing more than willpower and fairy dust. This is a movie in service of that kind of story that wants to continually and always be moving towards aspiration and inspiration, and away from anything that may temporarily stop the velocity and progression of that feeling. Even when the direction and script and Will himself desire to push for something greater its as if his own face betrays him, when he says “What you want a thank you” his face doesn’t give the power necessary to push that sentiment that sense of betrayal and anger into the realm of something as mean and discouraging as it needs to be.. Hes still half smiling and it’s not that devilishly slimy smile folks like Denzel and Willem Dafoe have mastered its just a weird stalemate between what he wants to do and what he's trained himself all too well to do over the years…

It doesn't do much for story that wants to be much more nuanced about the egotism and audacity of a black man who wants the best both for himself and his daughters and the hardships of doing that in an extremely white world or space. King Richard, like so many movies today, does not trust us the audience with the ability to handle impactful and crushing turns in the story, it doesn't trust us to be able to handle impactful and crushing turns in a character whom we like. So that unlike 1995's “Jerry Maguire” where we see even a positive decision like Jerry deciding to back Rod Tidwell and take him around a convention in order to boost his contract, - King Richard won't let us see its version of that turn and smack to Jerry in the face from a racist father who viewed that as a shunning. In the case of Will Smith as Richard it won't allow us to see as 1994's “Jason's lyric” did Bokeem Woodbine - the idea that he or even Forrest Whitaker's “Mad Dog” could be both very sweet men and very terrifying men at the same time. This lacking hobbles and impedes any true resonance, and in respect to Richard's personality in story- it fails as we actually never see a consequence to his egotism to his stubbornness or someplace where we would see he wasn't right to make this decision. Script wise almost every single decision he seems to make in this movie goes in his favor so how are we to ever really impactfully see what and how his stubbornness hurts those around him when even they don't really provide any consequence to his behavior. This lack of trust breaks a bond between audience and art. It’s art that ensconces itself from our disappointment in a way that keeps it safe by disallowing us to tie ourselves to that more closely in a way that might allow us to become angered or incensed at the work, especially that part of the audience that is actually apart of its story in the Williams family. Sure we end up liking, maybe even loving it on some superficial level, but ultimately it leaves us at a distance, that same distance that has always been kept between us and its star Will Smith. It doesn't invite us in for any real discovery about Richard Williams or about Will Smith and that is still sad in this time because we don't need biopics that provide such sterile and curated depictions of our heroes in order to protect them or find their power anymore than Richard needed to provide such a sterile, heavily curated environment for his kids to protect them or find their power. What we are left with is a movie that mines nothing except visual confirmation of things we already know, brings no deep emotional discovery or excavation and like its star ends as extremely likable, but mot much else, and also like its star I wager even that will change with time.

Dean Stockwell: The Gate.

/When I was young I didnt have much of a grip on reality. I didn't care for it much either, what was there just didnt interest me much. I believed very much in worlds that bordered ours, and in heavens and hells, and dimensions, and that imagination found several confirmations and vessels in various forms. There were bent trees over large fields whose brush touched the ground as the roots knelt in it. There were my pencils and pens which drew on paper and in the air, secret doors like in CS Lewis's definitive childrens Chronicles -to these alternate universes, and then there were actors whom I fixated on as obvious occupants from these various worlds who acted as gateways. One such actor was Dean Stockwell whom I first discovered in David Lynch's fever dream adaptation of Frank Herbert's essential Science fiction text “Dune”. I didnt care or even know about the movie as a box office failure or whether it hot the text right, I saw it and Stockwell in it as further visual proof of the otherworldly, and fully grown I still think so.

I've seen David Lynch's lynch's “Blue Velvet” probably 4 times, it's possible it's 5 over my life, but like most of lynch's films save for Dune, I could not tell you still what that movie is about and whenever I recall it it comes to me more so as a collection of scenes and images than it does a coherent idea or feeling about the film. Of course one of those images or scenes is iconic and burned into I think most peoples memories. It's the “Roy Orbison” scene in which Dean Stockwell occupies a certain space a certain time that feels disconnected even for Lynch from the rest of the film which felt like a hostage movie on LSD. In a TCM interview avaiable on YouTube, Stockwell tells the story of how his work on Francis Ford Coppola's “Tucker: The Man and His Dream" came to to be. He tells of Coppola giving him 3 pages with 3 varying iterations with varying intensity of the short scene in which he would play fellow dreamer Howard Hughes. Coppola then allowed him something most directors don’t, he told him that he could put together these pages in any way he wished and he said that he basically didn't see him ( Coppola ) again for 3 weeks or so and wrote it himself and in exactly the way he wanted. It plays like a dream, and he plays as if he is already a ghost of himself come to visit Tucker. He speaks in a drawl soaked in Texas and distance, a deliberateness that borders on being android like. Maybe he hails from another world, place, time, dimension, whatever you want to call it, but once again it feels both foreign and at home. Back in the interview Stockwell called Coppola “dreamy” as a director almost immediately followed by naming Lynch as the same. By “same” he means he was again allowed to create his own character through invention with very little to no intervention. In a PIECE on Stockwell's role as “Ben" by the unassailably brilliant Sheila O Malley, she writes : “The script said NOTHING about him. Lynch knew that whatever Stockwell came up with, in terms of inventing Ben, was going to be great – he just trusted him with the character (a rare thing. Most writers and directors OVER explain characters because they’re nervous that the pesky little actors are going to be ruin everything with their interpretation).Stockwell went to work. He created that guy’s look on his own – the makeup, the clothes, the energy … He hasn’t made too many mistakes in his career. He hasn’t over-reached, or missed the mark too much in his 100 plus films, which is quite a record. Who has seen Blue Velvet and doesn’t remember Ben? Not possible. Also – doesn’t it seem as though Ben HAD to have been written that way? The whole character seems completely inevitable … and perfect. Of course he wears makeup, of course he dresses like that, of course he stands around in large groups with his eyes closed – communing with candy-colored clowns in the ether of his brain. But no: none of it was set out in the script. Stockwell MADE that guy. I think that is so hysterical, so wonderful. It must have been such fun.” She was right and Stockwell confirms. I saw blue velvet for the 1st time when I was 19 I concluded that his character was an alien and I see nothing haven't watched a few more times to change my mind, but This was always the space that Stockwell occupied for me it was coded within his acting as it spoke to me. For me Stockwell was kind of born to play with somebody like Lynch because as an actor he always made choices that seemed foreign to any idea of space and time, but not so far that he also never knew how to find some way back to the path, whatever path of whomever was directing him - back to the world in which this character needed to occupy. A prime example exists in the lead up to the Orbison Karaoke, Stockwell stands being a gracious but equally weird host to the very outlandish Frank Booth. While Hopper goes off doing his very best Hopper, each one of the surrounding actors giving different beats he kind of just disappears. Theres this strange minute where he closes his eyes and he keeps them closed as if he just teleported himself somewhere else. It occurs at around the 2:50 second mark here and ends at around 3:15.

Where did he go I wonder? Was he like younger me in commune, and attuned with places that we're outside this particular rental space we call reality? Could he conjure them up at a moments notice? What did he find there? A time limit? The way he comes back is like a stop watch, it’s not just Hopper’s words it’s a suddenness that implies a condition, and that implied to me an alien-ness. Whatever it was, whatever he found is inconsequential to the film, but vitally important to the character of Ben and his place in it . It also displays another important facet of of Stockwell's career and to his own particular magic and that is his peculiar understanding of the importance of a closed and opened eye. Sheila notices it too. I latched onto it instantly as a kid watching what is still one of my ga favorite movies and sequels, Beverly Hills Cop II. Most actors understand the importance of an open line but the widening of the or the closing of especially of a especially as something that I've never seen deployed and quite the way that Stockwell does it. Only one actor I could think of right off top understands this in anyway like Stockwell, though to completely different effects and purpose and that is Samuel L Jackson. In the Blue Velvet scene you'll notice Stockwell likes to widen his eyes upon certain words for effect, or close them on another's and almost a glare like state that underlines his characters mental state, but also his sense of the dramatic. You then watch Beverly Hills Cop II, which is completely different movie and you seem the same thing, despite the fact that you couldn't find two more vastly different characters with vastly different motivations, it totally works. As deployed in several completely different ways distinctive from each other it feels vital to the ideation of Charles Kane.

When he delivers the line “Adrianos was perfect” he opens his eyes, and then closes them not fully, but into a glare in one fluid motion. It suggests a sort of confusion, and an indignance in concert with his enunciation, it evokes ego, but carefulness. Not but a few moments later as Jurgen Prochnow insults him he does it again, but this time it indicates a slight tinge of hurt, propelled forth by his pride, which bades him to listen further rather than immediately go on the defensive. When he does it again at around 1:34 it’s pure delight in his own work. He just knows it was great work, and that pride extends beyond the context of character. Stockwell always came off as an actor who took immense pride in his work and that is not to suggest he was proud of every single one that he did, but that in the actual doing he took a certain pride and it's at least one of the reasons why in his entire career which is a very long, extending from his childhood to the 00's especially as he starts to formulate as an adult I don't find a bit of work that I don't enjoy from him. But more importantly what connected me personally to Stockwell was the distance he maintained from this sort of homogenized idea of not only performance but humanity that provided this consistent and persistent sense of other worldliness. It's at home and and it belongs to everyone of his most memorable characters whether on TV as Al Calavicci in “Quantum Leap”or in a film like Tucker this sense of the fantastic, of pure fantasy. His eyes would act as the window to another world, his mouth as an anchor to this one and he was always able to in any number of roles transport us, transcend us, but never without emotion never without structure and never without power. Stockwell in that same TCM interview talks of the loss in a certain aspect of his childhood in the movies, one that he wouldn't wish upon his own children and I've always had the feeling that when something like that happens it's not really that it is lost, but that it is stunted and then continued along a slower trajectory. In that context it's no wonder the Dean appeals to me on a bone-deep level, me a person who now deels not fully separate, but veiled away from that weirdness I was so in touch with, so in love with when I was a child but I let go of in order to safely fit within the world around me. That same alien alien-ness that is so much apart of who I am, that I only find whenever I'm on stage, or behind a camera when and where I’m given freedom to imagine once again the infinite possibilities of my own humanity. That's what a Stockwell performance is to me, A doorway, an opening, a link to a distant place, but right within your home.

On Crying.

/Tom Cruise breaks down in Paul Thomas Anderson's “magnolia”

Brilliant filmmaker and Twitter mind Kyle Alex Brett (@kyalbr on Twitter) and filmmaking genius Abbas Kiarostami are and were ( In Kiarostami's case) the kind of people that stir in other people what they believe they’ve forgotten. You may have noted it, you’ve definitely seen or observed what it is they display in their one-of-a-kind focus, but it’s not until you see it from their own uniquely esoteric angle that you recognize all that you observed but forgotten, simply because they can see it real time in moment, and recognize and relay as much almost as if they’ve frozen the thing in time to observe and analyze, to feel…such is their focus, their gift. It’s an example of one of the foundational aspects of great directors to me to find the universality in the esoteric. This time it this connection was excavated by a small Twitter thread from Kyle where he elaborated amd theorized about our emotive connection to film after reading a passage from Kiarostami's book. The particular passage's subject; editing, kyle’s focus; crying as a primal urge. Kiarostami's and subsequently Kyle's words got me to thinking about crying, and then to some extent about Men crying. About its power, about when, about why, and about whom. In Kiarostami's book “Lessons with Kiarostami”. The passage read “I keep what I think is good and I throw away everything else. Sometimes the best thing is to remove a shot, even one you have worked hard on, because it turns out to be foreign to everything around it. I might discard a moment when an actors performance is too powerful, or a particularly interesting improvised line or interaction between two character emerges. These are the kinds of things that can distract an audience and overwhelm a film.” Skipping forward he goes on to say “The most effective tear doesn't run down the cheek it glistens in the eye”. In its entirety its a powerful statement not only in its simplicity, but in how it speaks to Kiarostami's style and exemplifies how in the most classical sense of the word Kiarostami is an autuer. There are very few filmmakers whose films are quite singularly their own as Kiarostami, very few who in this very collaborative field of work can say their fingerprint is so acutely successful, not so much for dollars and cents as for nailing down the most detailed minutae of the human experience. I then got to thinking about whether or not for me it is more moving to watch people hold back tears, or let them go. That got me to thinking about whom, and that got me to thinking about the “why's", my answer - typical of my median nature was “it depends”, and then it was also that that “depends” has alot to do with socialization, and I suspect I’m not alone. It’s definitely nobody's secret that men are conditioned far than women to repress emotions, especially crying, and even then 0ne would have to take in and assume cultural differences. Me being an African American makes my experience of what effects me different than what effects Kiarostami, even while there are universal aspects that undoubtedly connect and effect all of us. In that spirit I find what makes men cry, and even moreso men crying 9n screen particularly interesting because in my mind it’s is so rare, far too rare indeed to think of men in real life or thusly film as somewhat of a representation of aspects of human life- giving themselves over to and allowing themselves the sort of catharsis that comes from actually crying rather than the usual which is the form of repression that Kyle would allude to later in his thread, and that to some extent represents itself in Kiarostami's words.

When I thought about all the films I could recall where men do some version of crying, even looking up others so I could find more and recall the emotions- the most effective ones had a range of depictions and looks, and rightfully so because the key words in what Kiarostami says are “turns out to be foreign to everything around it". For instance in the seminal scene from “Get Out” when Daniel Kaluuya's Chris Washington is first introduced to Missy Armitage's (Catherine Keener) “Therapy” it would've been absolutely distracting to have him ugly cry, rather than well up, but tears do roll down his cheek even as he tries to hold them back, but as Kiarostami alludes to the power begins at the glistening of the eye. It alludes to the power of this story and the hold it has on Chris. He could very well have cried and cried hard, but that would displace the power and that would be release and release is not about relinquishing power, it’s about letting go to redistribute it somewhere else.. namely back into self rather than the people or things which hold power over us. But there is also the fact that despite his efforts the the tear comes rolling down the cheek anyway, that is powerlessness. The memory of his mother holds power over Chris, and Keener's Missy understands this and being who she is uses it to hold power over him as well. To have him let go would then not only be distracting, but wrong for the scene.

Where it gets interesting is when you change the dynamics around anyone scene regardless of gender. Now, the first thing that popped in my head reading the quote was the power of watching Tom Hanks absolutely lose it over a damn volleyball in “Castaway”. On its face it sounds silly and like the last thing one would expect any man to cry over, but it is the conditions that lead up to it that make it at home with itself as the only and best representation of that primal urge, and it is one of the most timeless scenes in movie history. The loss of “Wilson” would absolutely have been dimmed by merely having Hanks merely well up rather than go full on ugly cry - but I digress… I decided to go elsewhere and revisit a scene I hadn’t seen in forever because the movie (Good Will Hunting ) was a movie I watched way too much when I was younger, and I had some feeling of unnerving dread that if I watched it again it would not age well… I watched the scene on YouTube for research and well, I need to re-watch this movie. While I don’t know about how the rest of the movie will ultimately come off, the “It’s not your fault” scene was intensely effective, and every bit as powerful and arresting as when I first saw it. Re-watching the scene with none of the erected context that led to it, I somehow still ended up legit crying…not a lump in the throat, not a welling up the eyes, a pure unadulterated holding my hand over my mouth ugly cry…

The dynamics of the scene are about the dynamics of interpersonal relationships between men, fathers and sons and friends. It calls forth my own memories of my relationship with my father, even while I did not endure that type of abuse, the artiface of the conditions do not matter simply the emotional underpinnings. The scene is almost a functioning call and response that forces us to look at the space we hold for each other to be each other, to be our most authentic selves. What Robin does for Matt, what Sean does for Will, and the movie for us is provide catharsis by way of a subjective experience that connects objectively. The dynamics of what makes us cry and subsequently (being that we are all built on such unique and yet similar foundations) what might qualify as the most brilliant and useful technique in getting us and let’s face it especially men - to break our generally well guarded fortresses of composure and facade is endlessly fascinating to me, and of course it would be Kiarostami, whose career put human emotion under a cinematic microscope, who would offer such an audaciously concise formulation on the most powerful form of said emotion while still allowing for a complexity of the factors put together to create it, all while outlining a simplicity to his own processes. Mine own most powerful moments align with those stated in Dolf Zillman's “Excitation Transfer Theory”. In it Zillman goes on to provide the pathway to the emotive connective tissue between us and the movies that bring out such strong and intense feelings in us. He explains what sets us up; “At one time or another, everybody seems to have experienced the extraordinary intensity of frustration after rousing efforts, of joy upon the sudden resolution of nagging annoyances, of gaiety after unfounded apprehensions, or for that matter, of sexual pleasures in making up after acute conflict.” What knocks us down; “Excitation in response to particular stimuli…is bound to enter into subsequent experiences…Moreover, depending on the strength of the initial excitatory reaction and the time, separation of emotions elicited at later times, residual excitation may intensify experiences further down the line.” and why it sticks with us after; “Emotions evoked in actuality by personal success or failure are usually allowed to run their course. A person, after achieving an important goal, may be ecstatic for minutes and jubilant for hours. Alternatively, a grievous experience may foster despair or sadness that similarly persists for comparatively long periods of time”.

Anna Karina's tearing up at the sight of Renée Jeanne Falconetti's performance as Joan of Arc in Carl Dreyer's is both a perfect example of the exact power Kiarostami alludes to, and a fascinating Russian Nesting Doll of the factors that exist to create our relationship to emotive catharsis and release through movie going. Does Karina see herself in Joan? Probably not, does she recognize in the aesthetics of Joan’s pain a certain appeal to her own, maybe? Whatever the reason Anna's own release as a response to stimuli that stimulated her own subjective experience, is so near objectively powerful that it itself became as recognizable and powerful a moment as the film it pays homage to and the particular scene that she was watching. The experience so relatable watching it becomes an experience itself. Nonetheless the factors around it that lead up to it , our own collective recognition, be it conscious or not that’s the killer knockdown, that’s the “Love TKO”. Much like a TKO it’s the build up that matters, the set ups, the small build-up of hits to the body, and wear on the mind that setup the knockout. Whether it’s an aggressively ugly cry or a suspended tear in the corner of the eye, it is what the storytelling has set up before that matters most. It’s the “everything around it" that Kiarostami spoke to. When I watch “Castaway” it’s the everything around Hanks endearing relationship with an inanimate object that became the embodiment of Hanks journey, and a security blanket for his feelings of intense isolation and loneliness that created a directline of passage for which the tears could fall down. The sight of watching all that float away when we do not yet know if he's even going to make it, finds it own subjective nesting place in the cradles of our own recognition of feelings of abandonment, loss, loneliness, and fear. The cry itself is in my opinion not so much a choice as it is itself an almost involuntary and intrusive response. The director is after all an audience member as well, and the actor and director are actively, simultaneously conjuring, responding and creating the stimuli by which they will both respond to in a way that I believe provided them with their own sense of catharsis and release consciously or not. The result is Hanks breaking completely down, and Zemeckis recognizing the moment itself as a proper realization of the created moment by way of his response to it, his own version of “Kiarostami's “what he thinks is good” turns out to be a pretty universal experience of good, hell..GREAT.

The socialization of Men to view crying as directly associated with femininity and femininity itself as an state of inferior otherness rather than a natural aspect of our complex and complete humanity leaves men at an interesting interaction of the conversation because any peek into an acting class will demonstrate how much more difficult it seems to be for men to cry on cue, and to properly crest and create within themselves the conditions that will allow them to act in such a way that it feels authentic. That sits parallel to the male audience member who may find repulsion at the sight of the the breakdown of the social barriers that protect them from the social rot of such a gross display of femininity. But the body and mind respond nonetheless, because the body and mind- even the socialized mind -subconsciously recognize what we may choose to repress. That being the case I ask myself how much of Kiarostami's feelings on the superiority of that particular type of display of emotion have to do with his own unique cultural socialization? Even while also being aware many a woman might also find this to be the superior form of emotional display on screen. The Conversation in my head could go on and on deeper and deeper, but ultimately what works on screen, what surpasses the realm of the superficial emotion, and steps beyond the border of profound emotional content as it regards one of the most fascinating and singular aspects of humanity - the ability to cry is endlessly complex and I feel exactly as Kiarostami feels in regards to getting there as an actor, as a director, and as an audience member keep and hold onto what is good and throw away everything else.

Yaphet Kotto: Don't Act, Just Be.

/I once remember watching a Turner Classic Movies dedication to Katharine Hepburn in which Anthony Hopkins said that while working on the set of “The Lion in Winter” the great gave him a wonderful piece of advice, she told him “Don't act, read the lines, just be, just speak the lines”. It's a very specific piece of advice for a very specific type of actor of which Katherine Hepburn was, Anthony Hopkins is, and now Yaphet Kotto was. Yaphet Kotto enjoyed one of the greatest careers I think anybody so clearly held back by the industry has ever enjoyed. He got a bevy of unique and varied roles which allowed Kotto to flex his acting muscles in different ways, whether it be using his full 6ft 3 frame, his elegant way of movement, or his effortless way of speaking, and many times all three. Its the speaking part though that is my favorite part or talking point in regards to discussing Yaphet Kotto, because it plays so much into how Kotto's legacy engraved itself into our collective consciousness. Kotto like Hepburn, Hopkins, John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, was an extension of that fold of actor where all the lines or the words find their meaning in the throat of the actor. The “heady actor” divines the meaning in the words, the “transformative actor” twists, bends and conforms the words to their will, the “straight shooter” just aims and fires, let’s the words find their target….and yes I made all those terms up. It has been spoken about many times, but far too many people have a disdain for actors who speak plainly, who in essence as Hepburn said don’t” act.” If it's not John Wayne it's Hepburn, or its Bruce Willis, Sam Jackson, or the Rock, but what's missed is in the case of all of these actors (and of course in varying degrees) there is an extreme degree of difficulty in just being. Number one, it must be said that from the moment an actor arrives on stage, or in front of the camera - there is almost instantaneously this need to be someone other than oneself. You realize we're here, that we are watching you, and all of a sudden every fiber of your being is telling you we can see right through you, we can hear you not being an actor and you need to emphasize more, or maybe that last word needs more accompanying face because yours , well that’s just plain silly. People are watching everywhere and all of a sudden all of the lessons that the world has taught you in that you yourself are not enough - arrive fully formed at your doorstep, and a great deal larger than yourself usually. These feelings of immense doubt and self deprecation growl and swipe at you, and you stand there and do what comes natural to do which is to defend yourself, and in comes all these elaborate techniques and ways to hide yourself, make yourself better, to make yourself appear larger, and before you know it you’re acting, just not…well. The most difficult questions for the actor are based in and around building at least a very good edifice of comfort in oneself to the point where you stop looking to be larger than, smaller than, more important than, and you just trust that you already these things. Now as for number the small aspect, this is made all that much more difficult when you add the politics of being black and let me be frank “Ugly” and then the politics of being black and “ugly” in Hollywood in the era in which Yaphet Kotto was to break into Hollywood. I don't use the word ugly lightly, and most definitely not objectively, but I do use it plainly, because it is what many people including black people themselves would call someone who looks like Kotto were he not an actor. The politics and the indoctrination of anti blackness, that hatred for blackness especially overt and explicit blackness in and around the body in America, are well documented. Yet somewhere in his childhood growing up maybe possibly watching the very white idols of a former generation - the Montgomery Clifts, the Marlon Brando's, the Gary Cooper's this child and then man had the audacity to want to join them on screen. Where does such boldness come from? To stand and affirm oneself, to push so boldly against what remains unseen, to place ones strengths and weaknesses bare in front of so many? .. only God knows, but it's extremely affecting when you watch it, and alluring in that Kotto found something beyond the superficial aspects of our underlying desires to be or be with those we watch on screen, he and others liked him forced us to reckon with our attraction to what we disdain, what we are told to dislike. In “Bone”(1972) he plays just this ..the avatar of americas deep obsession with, its fascination and love of all things black and its hatred. He is there to pull on and from what may or may not have ever existed. A white man insist that he sees a rat, his wife does not see a rat, when the camera pans to the pool where the rat supposedly is WE don't see a rat, but when Bone arrives literally out of nowhere he sticks his hand in the water and pulls from the blackness just that a rat. Kotto plays this as a secret only hes in on, even though the white man swore he had seen it too, it’s as if he knows it’s not there but that he can conjure it. There's a quiet sureness to his gaze which he holds that exists squarely in that special place between threat and sensuality. Bone knows, and because he too is a conjured idea of the white man’s fear and hia wifes lust ans this is all in movie, but its lifeless until Kotto erects it. That was his appeal to lean on, to pull us in, to mesmerize us with, and in so doing helped open our eyes to the possibilities for masculinity and desire if only we were so inclined. Whether in “Bone” or “Live and Let Die" he found a “constantly evolving before your eyes” concoction of raw power, sexuality, grace, and confidence that rent asunder many of the standing expectations of a man, a black man such as himself, and its extremely audacious and extremely effective much like his Bond Villian Mister Big…yeah that’s Yaphet ..Mister Big…

I was scrolling my Twitter timeline the other day and I fell on an interesting tweet where someone speaking about Anne Hathaway said “She always understands the assignment”. Once I got off thinking about whether or not it was true, I started to think about that particular usage of words, and how much I really liked it.. “always understands the assignment” - It's a vital integral aspect to acting. Amongst the great separators between the greats and the So So's. There are quite a few actors who I believe are quite good at what they do on paper, they have all the goods, but consistently they misunderstand the assignment, that is - what the role needs with the role calls for, and their interpretation of the role. Many times I've seen performers who are actually not that good become so good in a role that they become somewhat overrated as an actor - as it pertains to their skill level or the skill level involved with the work - simply because they were so good at understanding assignment! Thats the power of that factor. Think recently of Adam Sandler in “Uncut Gems”. In my opinion it's not so much that the man is so great in this role as far as the actual attributes important to acting, it's that he understands the assignment so well, so deeply, thqt it organically melded to everything he already had in him and it functions on a level akin to symbiosis. It's what many refer to as being born for a role in that there just weren't that many people who could cater to that role in the way Adam Sandler could and that's not to take away from him because part of that is that he had an imagination. He saw it so clearly, understood it so clearly and there are a lot of other actors who some might deem more intelligent, better actors who I think would absolutely fumble this because they'd overanalyze it, think it to death, or just dont have what Sandler has that kinetic, nervous energy alwaya coiled rans ready to bute has really been apart of hia entire brand for years, its very specifically his and only his and anything less might’ve ruined it, - With Yaphet though this specific attribute was not a one or two ( If you consider Punch Drunk Love another) time happening, it was his career. I've seen a lot of his films “Live and Let Die” “Alien” “Brubaker” “Across 110th Street” and lesser seen ones like “Bone” and “Friday Foster”. I've never seen one role, one word where it seems the Yaphet Kotto did not understand the assignment. Ridley Scott's Sci-fi horror classic “Alien” is the most ready made example of this, I think it’s why his role in it resonated with so many. There's a quality to the character Parker I think is built into the script. Class wise most of the crew is ambiguous at best, they could come from a wide range of backgrounds but it's Parker, Lambert, ( an under discussed Veronica Cartwright) and his partner in crime “Brett” (Harry Dean Stanton) that come closest to basically putting out a large neon sign that says blue collar.. working class. No one seems to get it more than Yaphet, its what separates him, not only understanding his class, but his blackness, but not forcing it, just letting it breathe it’s own life into the role. Perhaps coming directly off of Paul Scrader's magnificent “Blue Collar” just one year earlier he brought some of what he had there straight into the set here. The artifice is there - in the details; the bandana around the head the open shirt, the lack of any respect for decorum, that's the superficial calls to class, which many times in our collective minds has to do with our indoctrinations around certain behaviors mainly a sort of coded rigidity versus in openness and freeness, on the “Nostromo” you can almost rank their class and rank by just how open their shirts are . The blackness though is deeper, or maybe less noticeable I mean, but still very clear to the initiated, its in the way he checks folks, the seriousness about his money. Its in the fear he shows, how it registers in his body, it could be anybody but it reads as definitely black that's not just represented in the words that he mouths, but the way that he mouths them, and the body language that accompanies it. Its comforting to watch blackness flourish in a mostly white film without being embellished upon. I'm reminded of another role that I love and which a black man is surrounded by white people where his blackness is affirmed while never being overtly expressed to in a way that seems mawkish or exploitive ..Ernie Hudson as Winston Zeddmore in 1984's “Ghostbusters”. In both these roles there is a relaxed authenticity to how these men interact with and stand apart from the world in which they are involved, they understand how the world sees them in this place, they may even nod to it, but never overtly condescending to us the audience or to themselves, they simply let it be …

The politics surrounding the body in regards to Hollywood is important, especially when speaking to or about careers. Hollywood was never completely a safe comfortable space for atypical looks, bodies, minds, for anyone but especially not anyone who wasn’t white and cis male, but if ever a time came as close to being somewhat relaxed in the physiology and ideology as to who and who couldn't be a leading man or matinee idol in the realm of looks it seemed the 70s was that. It was it’s own kind of incubator for counterculture of which cinema of course didnt escape. The strong-jawed Lancaster's, Grant's , Pecks, and Mitchum's had aged out, and different types of men were taking their place with differing types of sex appeal and masculinity. It was now Dustin Hoffman, Jack Nicholson, Al Pacino, Jon Voight, Robert Duvall. These men werent the apex of male bodies, many of them had strange faces, broad and lean, with asymmetrical properties. They could be balding, or fat, or lanky and awkward, they had the everyman quality of a Stewart or Joseph Cotton rather than the reverential beauty of a James Dean, Clift, or Roc Hudson, but as is always the case whatever happens to the white male in this society is not merely or easily transferred over to black men, so while the ideas around what constitutes beauty and masculinity was broadening as it pertained to white males, for black men, and any other group not cis white males it led to a large void if represented at all. The “Blaxploitation” movies provided a lot of would-be suitors for black straight appearing ( because who knows) cis men in Billy Dee Williams, Calvin Lockhart, Richard Roundtree, Glynn Turman, Fred Williams, and of course Yaphet, but Hollywood seemed much more hesitant and apprehensive to crowning any one of these men as a new leading man, and so that void pretty much remained until Denzel Washington arrives nearly a decade later. It says quite a lot for Yaphet that out of all of these men that it's Yaphet, blacker than all of them, somewhat portly, and atypical even while in truth being beautiful man- who arguably had the best career. To watch Kotto was always to watch a sort of mini revolution in my mind, infinitesimal, maybe subatomic, but it was nonetheless a revolution. Every Kotto appearance was a small act of defiance against the standard, the ideal, there were very few actors like him then, and there are still fewer now who look like him now in looks or abilities. I don't know anything about Kotto in firmness, I don't like to make large grand statements about representation or what seeing a black man who looks like Kotto on screen does for all black people, but it implies a lot about HIS survival skills, about HIS abilities, and to some extent about HIS confidence. Kotto was a bit of a conundrum like so many black actors, (especially from his time) in that it is only after they pass you find that all these people knew of them, that they were beloved and their work was deeply appreciated because for so long they live unspoken of. You go to Kotto's Wikipedia and it's almost farcical how small it is. You try to look up information online it's not much there. Homicide life on the street ends its run in 00’ and for 21 years this man has one credit to his name. Did he retire on his own volition? Did he just feel like he had nothing more to say, did Hollywood decide that for him? We don't know because it seemed very few people cared enough to want to ask Mister Kotto, yet on the day he dies, with no political affiliation to speak of or to, only small mentions of a legacy in civil rights work, no celebrity gossip, no books or memoirs no lifetime achievement awards or various ceremonies celebrating his career, there is an outpouring much larger than the man's actual career really would speak to, and you would be a fool to belive this outpouring disingenuous. You can feel it in the size of the words used around his name, and the frequency. That…THAT to me is his legacy.. that he just let things be, that he just existed and yet despite or maybe because of that the respect for him is larger than most actors could hope for being given the same variables and forces working against for them as Kotto. Whether it was his life, or the words that he spoke in film, he just seemed to let them speak for themselves, rather than trying to force some meaning upon either his life or the words, and in that right there is his power to rest in.

ON ACTING.

/I have been acting for now 14 years of my life. I've been to various conservatories and repertories and colleges, been destroyed by it and uplifted by it, but I've loved it and I’ve been mesmerized by it even longer, since I was a little boy watching classic movies with my father that featured Humphrey Bogart, George Saunders, Bette Davis, Cary Grant, or the 80s movies with Schwarzenegger, Keanu. My favorite actor growing up Denzel Washington. I knew then this was my favorite aspect of filmmaking, though I was to scared too even think about wanting to be an actor. Learning the craft though has definitively changed my perspective. It was Sanford Meisner's “On Acting" that first dramatically changed how I view, watch, and entertain actors, and on that journey, that sense of discovery, in that time spent being interested and curious about the work I noticed a divide between me and many of my compatriots and peers in criticism- most especially as it pertains to actors. The great and invaluable writer Angelica Jade Bastien has many times tweeted and spoke to the egregious nature of opinions on actors, the problem of which lies not in liking certain actors or disagreeing about performances, but in the constitution of the ideals behind it. The superficial nature of what warrants praise or condemnation for actors coming from those who watch tell us a lot about how little time many of the folk speaking spend making themselves knowledgeable about the craft. How much they depend purely upon their own perspective as an objective arbiter of truth in the work leads me to believe they feel acting is almost completely subjective. The way this continues to show up extends well beyond just critics and into the industry itself. To be honest most directors I hear talking on the subject clearly dont understand what actors do, they just know what they want, and if and when that meets with an unconscious bias around actors, or with the weird tangled ego of actors, the tensions in the relationship of these communal groups end up as yet another example of how people that share similarities can be disdainful of each other. The likes minds like the aforementioned Angelica Jade Bastien, or Dan Callahan & Sheila O'Malley, Matthew Zoller-Seitz and Danny Bowes are as far and few in-between, as the likes of a De Sica, Chaplin, Scorcese, Tarantino, or Eastwood in conducting precise understanding of acting even if they themselves do not study not practice. They do however pay close attention to what the actors do on screen in particular to produce an emotion, and they are keen at sensing bull**** and inauthenticity. They are the oddities on the subject, the rest are far too given to putting mustard on performances that overly rely on histrionics, or falling in love with a performance that relies too heavily on quietness or stillness when sometimes you need to go big, or coming down too hard and confusing stylized grandiosity with “hamming it up”. Acknowledging that history as a gauge or rather a bar is vital to discussing actors and their performances, having that bar, based on a philosophical and educated understanding of the craft rather than what amounts to mysticism allows you not to stumble into the celebration of mediocrity, having that bar, that standard allows you to get specific about what it is you’re seeing, and where exactly it lands on a spectrum rather than a this or that binary. One cannot simply just look at a performance in a vacuum without consideration of what the top tier level of that work looks like, might look like, several ways it could be performed. Without considering whether it's wth words powering it, or the actor, or both. Any and every performance involves several levels of technique, then they erase it or throw it away, you have to trust that it's there and let it go. and I don't know that I can name them all, I don't know that I could articulate them all, but I will endeavor to explain some here based on what I believe was important and vital to Denzel's performance as Malcolm X. And I'll start with presence, and take it even a step further and go power. To play a transcendent figure you yourself must be transcendent. It is what Stella Adler spoke of when she lamented ; “In our theater the actors often don't raise themselves to the level of the characters, they bring the great characters down to their level. I'm afraid we live in the world that celebrates smallness.” By the time he was cast as Malcolm X Denzel had already displayed a level of talent and grandiosity that called out to the masses in a very similar way to Malcolm X. You watch Glory and you see it, you felt it in him yelling “Tear it Up!” , in his antagonistic behavior towards Andre Braugher and the other characters, and of course in one of the most recognizable and memorable moments in movies, his single tear. He drew and draws your attention right through Morgan Freeman, and despite the fact that the star of the movie is Matthew Broderick. Stella Adler continues: “There was a time when to play Oedipus you had to be an important actor. Until 30 or 40 years ago to play any major role whether it was Hamlet or Willy Loman, you had to have size. Write this down: you have to develop size”. This is something fairly new to on screen actors like Thatcher or Kingsley, but something they can develop by continuing their work and taking work that ask them to take it to Spinal Taps very infamous “11”. As acting teacher Marilyn Fox once told me “You have to be willing and allowed as an actor to take it too far and then there understand that there is no such thing as too far because” she said “It is beyond those boundaries that you find the performance”. Let’s be VERY clear, Thatcher and Adir-Kingsley are extremely talented, and they are both clearly well trained. They had an elite level of understanding of what and who their characters were and their responsibility to them, but they do not yet have that elite level of magnetism of presence and of size, so they depended totally up on training and skill and understanding of the role, a role that is essentially about one of the most charismatic and large figures in American history. Even if you want to make them more vulnerable, make them more approachable, humanize them in a certain way, you cannot afford to lose that grandiosity. Denzel as Malcolm did all of those things, and he was HUGE. Riz Ahmed in “The Sound of Metal, has that magnetism. Ahmed has what I call a natural standing belief, and by standing belief I mean just standing there you believe anything Riz Ahmed has to say . There's a natural built-in sincerity to him that comes out in his acting so that no matter what he's trying to sell you- as long as he understands it, and as long as that understanding is somewhat built into the work - he’s very hard to ignore or disbelieve as a character . He is a vulnerable actor, and he is a great listener, and maybe most importantly he is willing or seems willing to unlearn. In a recent interview with Matthew Zoller-Seitz, Matt asked about Riz Ahmed's walk, Riz immediately went into talking about the forms of non-verbal communication, “So once you come to SURRENDER to the script and to the technical process of preparation you do find that your body is telling you in a different way". “Acting is in the doing” Sanford Meisner ( maybe my favorite of the acting teachers besides Hagen) once said, and Riz is a doer, if I had to pick an actor that was next after Lindo from what I’ve seen this year itd be Ahmed. If I had any advice for Mr. Ahmed it would be go bigger. This doesn't mean I want the man to play in a Scarface film, (though in actuality that might be very interesting) but it does mean I want to see him try on his particular strengths in a suit that calls attention to them in a way that gives him this very size to match his self awareness, and deep earnesty. I'm saying it would be cool interesting to watch him in a Michael Corleone type role. Al Pacino found alot of his size ( and this is long before he started to rely on a few histrionics himself) in that role - in his stillness, proving it’s not all about big things, but the character has to be big, every actor needs a “Hamlet“, a “Virginia Woolf" For Pacino it was Corleone. His size, it's there when he closes the door on Diane Keaton's “Kay", and it’s there when he burns a hole into her with his eyes just before he violently slaps her. Ahmed has this kind of quiet size at the very end of “The Sound of Metal” but to pardon and unintentional play of words- that film and that role are far too muted inherently and purposely to be the kind of role that I’m talking about. If there's anything killing this era of acting, its the style that is being preferred, this fetishization of small subtle acting. I want to be clear - this too can be very powerful and in many cases it's necessary, but when you look back into the wide pantheon of performances that whether a cinephile or not people dont stop talking about, the ones celebrated over and over and over again, I guarantee you, you think about 99% of them and one word you must associate with it is Big. Whether you thought of it or not, it's there. Size isn't just about yelling or exaggeration and the effect it has on the audience, (which I think sometimes gets too much credit becomes a easy way into getting or being celebrated) ultimately at its core it is about purpose and goes back to Greek Theater where these actors had to play to audiences in large amphitheaters. Many of them wore special shoes in order to enlarge themselves, large masks, that they might be better seen, and they spread their bodies and their voices out in very exaggerated motions, and their form of speaking became very exaggerated as well and their delivery very deliberate. When Whoopi Goldberg smiles in The Color Purple it’s a smile that can be seen from a distance. Large, grand, beautiful, her own little rebellion in the onscreen fishbowl. Jimmy Stewart throws his lanky gaunt and lithe frame across the room in a fit and bout of fiery indignation in Mr Smith goes to Washington ans then he collapses and its a seismic as the rest of the performance, its a grand overture a final swing for the fences, THATS what you should always feel when watching a performance. Watch Nicholson in A Few Good Men, or the Last Detail, doesn't matter thw role might be detailed and subtle, but Nicholson is gonna bring it to you with a hammer, go back a ways and everything about Gloria Swanson or Toshiro Mifune is large, impactful in either Sunset Blvd or Rashomon. Jack In One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Meryl Streep in Sophie's Choice, (it's quiet but she still a large) Mae West, Al Pacino,Bette Davis, Robert De Niro, James Earl Jones, Elizabeth Taylor, Angela Bassett, Marcello Mastroianni, Paul Richter, pick any one of these names pick their best role, you'll find something about it that has scope, a sense of gravitas, and most definitely a sense of size. I can bet on Delroy, because performances like this dont come around but so many times in any given time PERIOD. If Yuen, (who I have not seen yet in Minari) Boseman, Ahmed, and Lindo are the best male performances of the year ( they are) and if they are in the same category in the Oscars ( that should be debatable) some of the things that I feel have corrupted and muddied the waters of the decision-making of those who are discussing these performances is worthwhile as a discussion not necessarily for the subjective battle between these actors but for the actor, and for all actors. Acting and or actors as a subject or as people have been discussed terribly. Performance reduced down to it’s most gawdy and banal quality-likeability, personality, these things do matter but thr cache of celebrity has entered the sphere and convoluted any real idea of what actors actually do, what it is, ctaft is rarely discussed and a number of adjectives lonk together to describe the complete and total dominance of the subjective as if there are no defintive waya to look at performances. For quite some time -and I think the advent of social media has really brought to bare in ways that one might not been able to have perceived before - the lack of curiosity about the craft, the lack of care for the work, and the lack of understanding of what it is you’re watching and at times it borders on atrocious. This piece is a labor of love, and respect, because as a movie goer, and as an actor this is important to me, this is special to me.

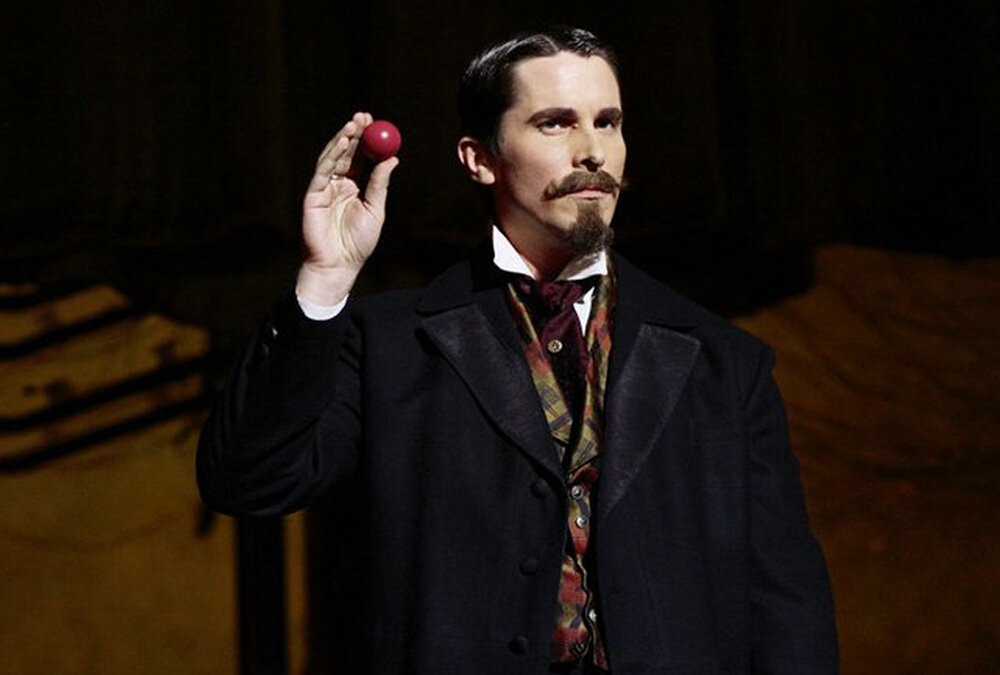

THE MAGIC ACT

One of the problems of the discourse that continues around actors is that there are very few people who in any real way understand what it is actors have to do. That is most people speak about actor performances in a way that is in the most classical sense of the word - selfish, self centered. It has so much more to do with how “I feel” about your performance, and less to do with the work involved in your performance, or the craft involved in your performance. It makes for the kind of takes that don’t draw the line between things rhe writing is doing and things the actor is bringing. So that we may like an actor like Tom Hardy and see a character that is pretty well defined by what he does, watch Hardy repeat and lean on his skills but also-ran tendencies and not critique that in his role in “The Revenant” which was really a continued repeat of the character he formed in movies like “Lawless” and nowhere near as revelatory or profound in what he found in his more interesting roles like “The Drop” or “Bronson”. More of that mumbling, lack of enunciation and his patent thousand yard stare, and so a slilled actor gives a somewhat distilled version of better work that mixed in with a great character, but unlike Sandler in Uncut Gems its not a discoverybof a new depth, its superficial. Roles like that become known partially because the focus becomes how the performance made “me” feel almost in total, and in that realm acting is completely subjective and thus any and every disagreement can be oversimplified as subjective, but there are as many ways to objectively grade acting as there are any other portion of the craft of filmmaking. The Last Dragon may be your favorite movie of all time, but most people who love that film ( Its ME, I’m most people) would hesitate to call it one of the greatest of all time without a sense of intentional irony or absurdity. This is because people have a sense of the history of filmmaking. They read and study even when they're not directors about the discipline. They go to Q& A's and lean on the words of directors and watch films especiallly to learn the quality of good filmmaking. It gets at and by process of elimination it implies almost directly the underlying problem and difference in how we view acting and especially I think American acting. I think it's at least worth noting culturally that European countries like France, Sweden, and of course England patronize and support the Arts and especially acting schools as a state function. Culturally they see it as a vital aspect of society. I think it's also worth noting that the Brits actually give out Knighthood to their actors! This is not to say that we should mimic this behavior, (personally I feel it’s a bit much) but it does tell us how important they see the art of that specific field. Here in America we've always had a conflicted relationship with actors. On the one hand we have at various occasions in our time bordered on deifying them. We hang on their every word, give them certain cultural and political abilities that they in fact might not and probably don't possess. We magnify their importance as overall people, but this is only when they become celebrities. The working actor does not enjoy this kind of a stage. A actor for the community is a joke, wasting his her or their life, and does not earn or command an iota of respect not even as a job holder. To this day acting as a career field is looked down upon as frivolous and flighty, the kind of pursuit not based in any real work, and that exists because of the divide between working as an amateur and a professional actor. Getting even the smallest paying job as an actor is difficult, because it’s not simply a job here, it’s not work. You are either on TV or on Broadway or your'e impractical and you're a bum Jules. I say that half in jest, using the quote from the diner dialogue in Pulp Fiction, but in many ways it's not that far off. All of this directly contributes to the mystification in an already murky institution, and in some areas the reduction of acting as a pursuit of craft, rather than of capital, which shows itself in all kinds of ways from the aforementioned lack of respect for the job to the erasure of the varying layers a performance. You don't have to be Jeff Bezos in order to be respected as the owner of a business - owning a small bar that does well in the town of the community would be well enough. Craft wise if a singer were to go on nothing but runs that feel exhaustive and overly performative most people can call that out but when an actor does a very similar thing many times in the public eye they're rewarded for it. The Divide between the amateur and professional shows itself in ways that present in the industry as a veteran professional actor being given far more adulation for poor or mid performances than they deserve. Denzel Washington most recently gave what I thought was a particularly lazy if not confused performance in “The Little Things” and still there were people saying that he was doing exceptional work there. If anybody else were acting like Denzel was acting in that movie they would get dragged from here to the amalfi coast and drowned, but its Denzel, and that is part of the problem. How little people know about what acting in a way makes it resemble magic. As a matter of fact many times what actors do is referred to as magic, whether talking about a sort of consequence of the effect, or their abilities. Many times it can be endearing, but I think it's dangerous in this respect; acting is not magic, it is a craft that actually depends upon knowledge, not ignorance for its effect. A craft of coming as close to truth as possible, as my acting coach once told me “acting is what you do out there, here you're here to give truth”. Acting is not (as commonly thought) about creating illusions, and unlike magic I don't think there should be so much of a mystery behind what actors do. Sure some actors believe in keeping some sort of mystery between their lives and their work but the work itself shouldn't be mysterious. Magicians depend upon the mystery of their work if you know what goes on in the act it is immediately ruined, but that's not the case with acting in fact I would argue the more we know about what actors do and what they have to do then the better the act becomes.

BE CURIOUS

This YouTube video of Michael Caine teaching a class specifically on movie acting is an absolute gem and it's one of a few, if not maybe the only thing of its kind available on the internet, and that specifically speaks to, answers, reveals what goes into our understanding of acting, because understand movie acting is (in a number of ways that I can't afford to go into here) decidedly and explicitly different from stage acting (although I do HIGHLY recommend being on the stage at some point during a career). Around 15 minutes into the video he goes on to talk about the difference between movie stardom and movie acting but recommends knowing and understanding what movie stardom is and how it can work for you in movie acting. This is the kind of information a writer of a recent opinion piece on Angelina Jolie could have used before writing a devastatingly bad take on Angelina's career. Too many times in our current era actors celebrity is directly linked to the way that people see, and read their work. This writer was unable to separate how she saw Angelina's celebrity from how she saw Angelina's ability to act, which has for some time now been significantly better than much of the media has been willing to admit. You get the distinct feeling sometimes that to some it can feel as if one person has too much, and to give them yet another thing, to add yet another thing onto their list of abilities or accomplishments just feels like an admission of your own lacking. In other cases we make the mistake of being angry disgusted, repulsed, by the cultivated, curated celebrity of the person (Think Tom Cruise's cringy inauthenticity in his real life) and we let it affect our ability to look at their work objectively, he's a helluva an actor who deserves more respect. Hell, sometimes our viewing, our perception of an actor's celebrity or the being-in-the-public eye portion of their work starts to affect the acting portion of their own work. Johnny Depp and Gary Oldman are two whose troubles behind the scenes (and it's just a theory) have affected in Depp's case and are starting to affect in Oldman's their art. I think for some time in the American coverage and understanding of acting - stargazing has dulled our senses and our perception of acting. We spend much too much time glaring at their brilliance paying attention only to those who burn the brightest within a Hollywood construction of stardom. When if you really want to know what the craft of acting is about its those who are deemed the “Character actors” that maybe have the most to say, that maybe most reliably portray to us what the work is.. the honest work free from the shackles of what Michael Caine discusses here or the base saturated sort of curation that goes on behind trying to make a career. Some of what the all-time great movie stars, (and I mean not just the stars, but the ones who could actually act their asses off man) - some of the most important aspects of what they have/had you can't teach. You can't learn that megawatt, god given you’re born with it “something”, but you can learn how to be such a megawatt born with it version of yourself may you shine just like them. For example, for the most of us, you may not ever be as cool is Paul Newman (just ain't happening I don't know what to tell you) but you can be just as affecting and memorable as a Paul Newman if you just watch and learn from what George Kennedy is doing in “Cool Hand Luke” because thas exactly what he did. John Cazale, Ruth Gordon, Angela Lansbury, Loretta Devine, Debbie Morgan, Joseph Cotton, Ned Beatty, Harry Dean Stanton, Bill Cobbs, Andre Braugher have a lot more to say in the craft, about the work of an actor than many of the superstars we put so much time and attention into. In essence the superstar, the movie star is a construct, and much of what they do is larger example of what Michael Caine advises against in his scene direction when he tells the young man “You were doing that for an audience, you have to do it as if you’re doing it for a friend” The great great stars do or did some of both, but stardom always asks of you, tries to nudge you into some manner of inauthenticity, it’s one reason why so many struggle with it. Acting cannot be about playing for an audience, it can't be about placating an audience and when we write about it I don't think it should be strictly about the audience. There's something disconnected and off about careers spent grading and discussing actors ability to perform with very few questions asked over their history to build a foundational idea of what it is actors are looking to do and looking to accomplish over a wide variety of roles and characters overtime that would aid in an understanding of why actor A or B is falling short. I think we understand because so many people have been so curious in the past about what it is directors do a lot more. It's all those questions, and all those essays, in all those books, and all those interviews strictly talking about directing, about auteur theory, and style over substance that interacts with our own developed tastes that has led us to understand and have a basis for when we decide “this doesn't appeal to me”, “this does appeal to me”. When talking about actors that seems to run purely off of a very subjective sense of feeling and ultimately entitlement that lacks a foundational education. In any case all of this, whether actor or critic- points to two obvious tragedies; a lack of interest in self interrogation and a lack of interest in the work. The latter is my concern. There is a profound lack of interest - or curiosity rather -in what actors do in their process. A valid question to ask is if we don't even know what it was an actor's intention or goals were, or what kinds of intentions are typical to the asks of a given role over a period of time because that has rarely been asked - then how can we really say we know for sure whether actors performances are good or not? What Caine teaches the student about camera acting and the different asks of the stage and the camera, and why the performance becomes gradually better as he warms to the idea that Caine presents is amazing to watch and should pique curiosity about the many other ways actors find ways into character or work, how they arrive at what they do. Too many times when an actor goes on interview or press run the questions lean towards their private lives and praise of the work, but not curiosity about how they came to create the work, or an oral history of the craftsman portion of creation of the work. No one seems to care that much about what actors are doing besides how it makes them feel. The amount and kinds of BTS ( behind the scenes) videos and content about what a director is doing, how special effects are created or recently the boom in curiosity about cinematography as compared to behind the scenes content around actors backs up my assertion. The misconception that Heath Ledger's death was in some way related to his performance in The Dark Knight backs up my assertion. The long-standing demand for memoirs on actors that have very little to do with how they worked each one of the roles that made them the legends, the troubles of finding and making a connection with what kind if actor they want to be with what kind Hollywood sees them as, the fact that there's a video of Christian Bale screaming his head off about below-the-line technician getting in his sight line but very little about why that was important to him backs up my assertion. The far and wide crevice between the mention of autuer theory and who created the framework for direction and those who created the framework for acting the Stella Adler's, the Lee Strasbergs, the Uta Hagan's, and the Sanford Meisner's backs up my assertion.

COLLABORATION BETTERS ELABORATION