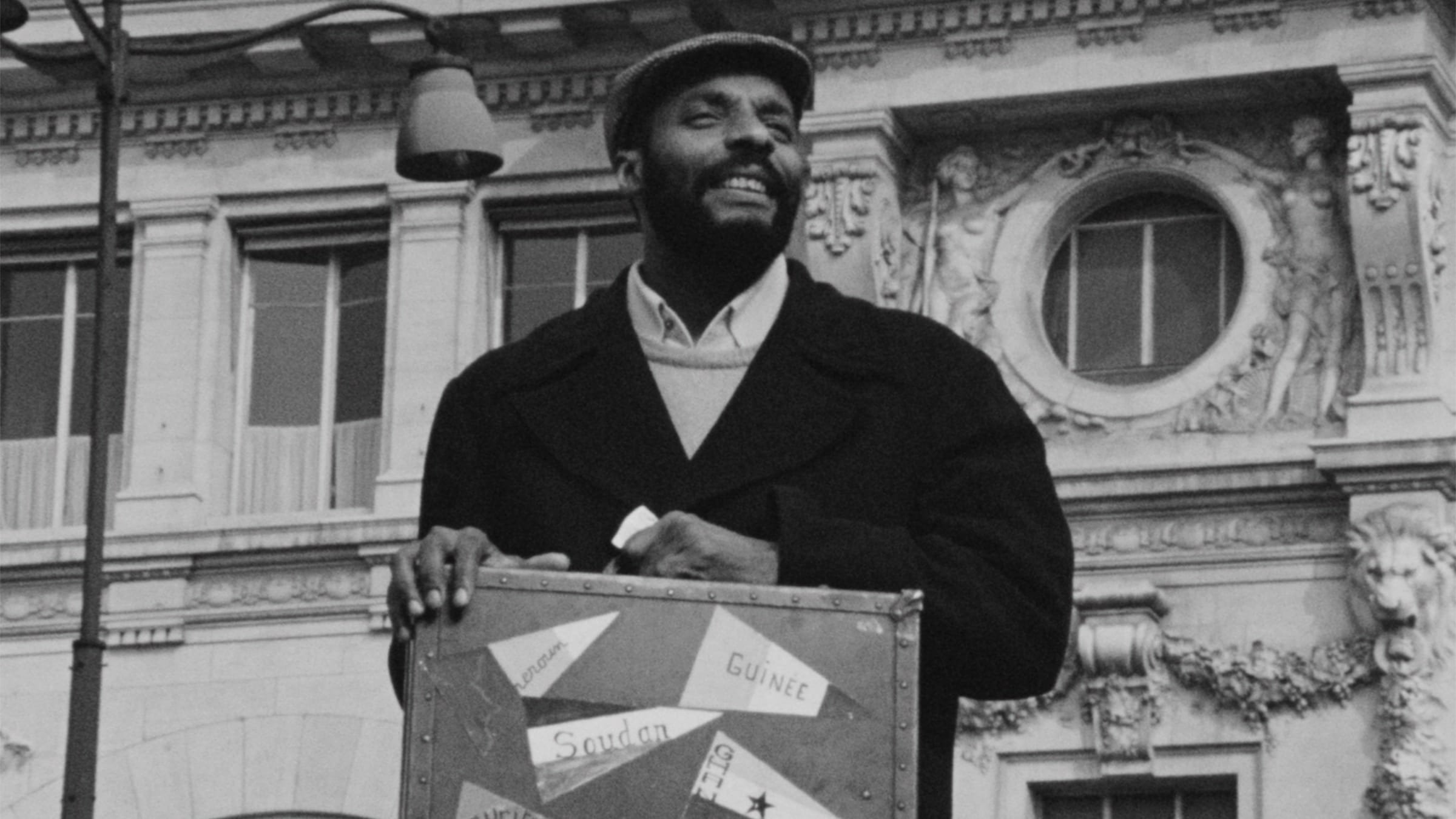

In Sembéne’s “Ceddo” a date is never said or mentioned, we have only a vague idea what period this takes place in, based off of costume and technology, but not much else. This is again intentional, as the lack of date implies the flux, or continuum of the behaviors and strategies on display. In Sembéne’s own words; “I can’t give a date. These events occurred in the 18th and 19th century and are still occurring”. In the epilogue of Gavras’s “Z” a reporter gives the news chronicling the events that happened beyond the reach of the film, when suddenly, he too disappears as we find out he was murdered from the voice of a woman. The time of his death is not acknowledged, the time that lives in between his absence is not acknowledged, because again time is not relevant to the actors nor the actions. In Hondo’s “Soleil O” we see a similar tactic to Sembéne's where a time is implied, but never stated and in Hondo's film we jump forward and back through time with no announcement or confirmation. One could be the other, the other the one. Uniforms change, clothing changes, but as with “Ceddo” ( which means the outsiders) the behaviors and strategies remain the same. “All truth is crooked, time itself is a circle”. The Nietzsche quote is not an argument as much as an invite to agitation and question. Time is meant to signal a great deal of things but in the historical context it is many times used to signal the beginning and ending of things. In that way time (a construct itself ) is a useful tool in the construction of propaganda and of a false sense of historicity that assumes that events of the past lived and died there, and the purveyors of it depend on that assumption. The radical nature of these films lie not only in the purity of the fire of their anger, or the straight forward force of their dedication to a deconstruction of truth - but in their resistance to the framework of time that allows the audience the peace of mind that comes with knowing this is not the here, the now, nor the present. Extending out beyond even the now of our own events (see Gaza, Congo, Tigray, Sudan, Haiti) to imply the future in the space of time between when these films were made, when the events occured, and now, which then leaves the audience with no safe place to go.