"Prey": We Didn't Need Another One Until We Did.

/If you were to ask me whether or not we needed to have any more “Predator” movies out there on general principle and based off of what we already have right now I would say no, but when you have an idea this interesting this unique that it almost flips the old property into an original idea then now you've got something and that “something” is what director Dan Trachtenberg found in “Prey”. Movies like this are exactly why I maintain the philosophy that there is a very tiny community of movies that I actually believe you can't do anymore of, or you shouldn't do anymore of. I simply ask if you're going to do them make sure you have an interesting way in...

The problem for instance with the latest iterations of other legacy films like the Star Wars films and the Terminator movies, If you look at them closely is anything that was changed for the most part in the new films is superficial, and aesthetic in the most surface way possible. Characters have new identities on the surface, but the core traits, arcs, and even the beats are still almost exactly the same. Rey in The Force Awakens is just a stand in for Luke, Poe is very much like Han and so on and so on. Very little is done to change what those movies were and more importantly what they can BE. The problem with the Terminator movies was much the same, an ardent refusal to go off the rails, to see what lies beyond the tracks already laid by the predecessor. This amounts to storytelling vampirism and much like vampires you can't feed off the dead, but with a movie like “Prey” what you have is that in almost every way that matters, This movie feels like an entirely different moving while maintaining the actual spirit and soul of what makes a predator movie a Predator MOVIE.

There is something more important than the “what” here and it is the “how” this movie “Prey” finds its way into telling a rich fun unique story that compliments and treasures the lore, but decidedly forges it's own path - That “how” is identity and culture. Much has been made of both the importance and the complications around identity and representation. As we argue for it we also reckon with the fact that representation alone is not enough. Throwing Amber Midthunder as “Naru” into this with the currency or cache still being around nothing but men telling a “man's” story with her as an inanimate prop would not have the power or profundity that this movie has. The “freshness” in Prey is in Midthunder herself and in the culture that surrounds and punctuates her choices as well as the films. The combination of a woman at the forefront of your movie and a woman of a particular identity in addition to her culture revitalizes and refreshes every possible angle and approach that we have. The Predator movies that have always mostly been about the triumph of individual man over beast and good ol’ American exceptionalism over everything now become a movie about the triumph of community over invading threat.

Near the beginning of the movie there is a scene where a member of the tribe is it is taken off by a lion, once Midthunder's character is alerted to the problem Midthunder's facial expression (pictured above ) elegantly folds into a distinctive portrayal of desperation, ambition, and hope. Midthunder as a performer has a sense of resolution that makes her perfect for a role like this. Her presence, her assuredness- effortless and well crafted- makes meals of scenes where she must take a stand or move past her fears. Its her moment and she knows it, but it's also just outside her reach thus the intensity of focus. Its representative of the kind of power that Midthunder has at her fingertips (especially of quiet expression) that this one look is so immersive and consequential that it acts as a setup of all of the stakes and all of the power of her eventual triumph. It was a high point for me but it was also just a part of a tapestry of performance from eyes to physicality that changes the entire energy of this film. What Midthunder brings as an actor to this role as the main protagonist of a “predator” movie is so different from anything we've seen in the lead role of a predator movie, then backing that you have what women bring that is always so distinctive from what happens when a man is in the role, and then her ethnic identity and her culture which is again so different from anything we've ever seen in these movies. Take for instance the fact that unlike all of the other “Predator” films and for that matter even “Alien” films that the tribe is not being picked off one by one in individual standoffs. Every time that we see the tribe being attacked by the predator they are together, it is always a communal experience, everything about this movie is rooted in a communal experience. From her relationship with her mother - to her relationship with her brother - to her relationship with the rest of the tribe, even while having a very charismatic lead whose POV we can funnel the movie through. In previous iterations the power of the movies were in each man going off to fight the predator alone seeking either personal glory in triumph or a Warrior's death, here the power is in the collective power of Naru and her tribes dedication to each other over all. Her final triumph is not merely an individual one, it is shown on screen to be the product of sacrifices by other tribesman, her mother Sumu’s (Stefany Mathias) medicinal teachings, and her brother Taabe’s (Dakota Beavers) instruction. I found it interesting to note the similarities in the role and Naru and the role of Emerald Haywood as played by KeKe Palmer in Jordan Peele’s “Nope”. Both young women who felt left out of their fathers legacy, both with deep connections to their brothers who do support them, both who triumph in major ways at the end.

The landscape in Prey as compared to the other films too is markedly different. In the other movies it felt more closed-in, more hot, darker even while taking place in the light of day. The jungle that always was a site for white tensions around fears they had about the peoples, became synonymous with “darkness” and “barbarity” and in that setting it only made sense that as much take place there. In “Prey” it is now the vast open plains and the “barbarians” are the civilized. It cannot be missed that this is one of what might be less than a handful of films told distinctly and ONLY from an indigenous POV. The value of this cannot be understated. It's why this movie feels so new even while revisiting the extremely familiar, but beyond that it's a reclamation of storytelling with the good being that it exists and the only one hope is that it opens doors for future indigenous to tell even more stories from their pov AND from behind the camera as well. As is Trachtenberg and co have done with privilege exactly what should be done while it exists, which is share decidedly in amplifying different stories, adventures, tales, with the added bonus being they almost inherently come with a refreshing coat of paint on past and future myths re-upholstering at the every least and reconstructing at the most the way we view and see other communities and the construction of America and what heroism looks like.

Misery: “This is So Good, Now Keep it Away”

/Misery is a movie I love to death and yet I find myself somewhat avoiding it, actually a lot avoiding it, just because when I think about it I can automatically recall the tension that comes in my body during the viewing of it, it’s absolutely fantastically miserable. There's the great performances in the movie that ultimately takes place in one setting for the most part and really between mostly two actors, and the way that the two work off of each other is almost a whole another piece I could write about in the “Actors POV” section of my blog. But this portion here is just to talk about the scenes I feel this movie does so well, and the way these scenes conjure up tension by giving us a protagonist who actually has what is commonly referred to as a brain, an antagonist who has the unflappable will of a terminator, and a closed setting that settles and unsettles. Also I want to kind of set up with some of my favorite and some of the worst things I see in horror. For example, I'm not as keen as I used to be on downing or judging characters in horror films for making bad decisions under what has to be considerable duress. You know that thing where a character keeps walking towards some strange sound in the night, and you yell “DON'T GO IN THERE!” and in your frustration begin to give up on the movie, because f*** this..Oh that’s just me? New me, I understand or try to understand that many of us on an occasion of meeting with things that do not jive with what we understand to be reality, would act as if that's not what's happening. In other words I’ve never seen anything resembling Freddy Krueger and/or Jason Voorhies and they would be the last things on my mind if things started seeming out of place in a real setting, whereas the audience in a movie is automatically in on the fact that this is a ghost story or story featuring a monster or some other terrible thing or terrible person, and additionally that even being in a movie theater is an agreement upon a break with reality. I have limits though as to how far I'm willing to deal with certain characters shenanigans and stupidity in film and this expresses itself in a very William Hurt “how could you f*** that up way. There's only so many times I can watch a person trip over s*** that ain't there, or put down a weapon after only stunning a person whose seemed nigh unstoppable and immovable in their desire to kill me, or reveal to an antagonist who obviously wants the worst for you and is already in a fragile place that you know what they're up to and you're going to get them when you don't so much as have a piece of broccoli in your hand to fight them with. Something else, (especially as I’ve gotten older I) I think about is the settings, the people, the environment. I like when films take place during the day instead of in the dark. I like when the antagonist is someone who seems charming or wonderful instead of instantly threatening and dastardly, and when the home it may be placed in is warm and inviting rather than dilapidated and rude. It does not mean that it automatically makes a horror films better that these things are there, but that when executed well it heightens the tension and fear to know that the places we normally deem as safe are not as safe as we have previously thought.

The Conjuring Rosemary's Baby The Shining and alien are examples of films that were sent in settings that weren't inherently scary or indicative of the whores that lighting either the places people or things. Shaking up our expectations that evil things are housed only in what looks evil.

In Misery writer William Goldman basically includes all of the above. The movie takes place mostly during the day and in an inviting town under the care of what initially seems like an inviting caring “Good Samaritan”. Much like that morphine Annie Wilkes (Kathy Bates) has hooked up to writer Paul Sheldon (James Caan) we slowly start getting drips of clues that reveal Annie is not what she seems until boom the whole thing is open, the artery is spouting blood, and we now know that she's a full-on demon. The town Annie Occupies is small, scenic, You watch a lot of other horror movies you'll see some form of a foreboding entry into a foreboding town in the movie. It might come by way of a gas station attendant who's leering, or a strange sky, or townsfolk like the family and the gas station member we met in Tobe Hooper's “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” ( Drew Goddard's Cabin in the Woods is also a great example of a movie that understands trope exists and then plays on it). These are the kind of sign post alerts that set the tone and put the audience in a mood so that by the time the scares are coming the audience is pretty much already set to jump, shudder, and holler, but in Misery they work harder to make us feel like he’s saved, not doomed, this despite the existence of trailers that told us who Annie was. This is proof that fear and all of its cousins are less about what we see, and more about how we feel. We're introduced to Annie Wilkes as a warm sensitive caring woman who happens to be one of his fans.. Little strange, little lonely, but nothing more, so despite me having seen this movie a million times even I am still somewhat drawn in by Annie original and unique charms, Bates does an uncanny job of playing a character whose evil takes on the same shape as her good. Later we are also introduced to Buster and his wife Virginia who qualify for me as one of the most charming couples in the history of movies besides maybe “Nick and Nora” in the Thin Man. The fact that the captor is sweet and the so too is the town she occupies recalibrates our thinking about the suggestions of where evil lives. That it's not necessarily in the midst of impoverished scenery or amongst disfigured or disabled people, that it can be amongst those who seem absolutely loving, the able bodied, and the status quo, all of whom in fact have a great deal of rage and evil hiding inside them.

There are two types of protagonist in horror movies I abhor on opposite sides of a spectrum, type A. is the type of protagonist in horror films who as far as I’m concerned lives or find themselves alive at the end almost completely by will of the pen, they win despite themselves, as if basically they had no business living if it were any truth to the matter but a deal was struck that guaranteed them life as a protagonist, so the bumbling idiot who has been warned by the house and seen various incarnations of the ghost or the monster doesn't die even though they continually go walking into the closet after they saw the little doll hop up off the shelf and “Jesse Owens” their way into the closet cackling and whispering to them “Come here I want to play” (clearly I’m not over this particular trauma). The other type is the person who either through forms of intelligence, feats of athleticism (pulling the martial arts out of their ass) or things that just don't click with everything that we've been told about them, survive damage that would irreparably harm them, or do things that just cant even be explained. So that character X who appeared in the last scene being stabbed into a human cheese grating block will now appear to save the day, even though they should’ve bled out in five minutes. As it were Paul in Misery is my favorite type of protagonist, dead center of the spectrum. Resourceful , witty, but fallible. Every single bit of tension in this movie, every time we are held in suspense or clenching our seat it is due to the obstacles that Paul as a normal human being has to try and overcome. The film thoughtfully considers that he is foreign to his surroundings and on top of that temporarily disabled. Annie Wilkes is a great foil opposite Paul because she is an unmovable force, and though the movie suggest Annie may not be the most intelligent in a “classic” sense many of us have been typically raised to view it, she is clearly intelligent, intelligent enough to think of a number of variations on how Paul might escape and to deceive others quite adeptly. Paul too is a thinker, but not one that seems unbelievable. He wants out, but is also not so drunk with the idea of getting out of there that he starts stumbling and tripping over himself to get to his destination, alerting Annie to exactly what it is he wants. I love every scene (and the way James Caan expresses this) where Paul attempts to appease Annie Wilkes and to be friendly and on board with all of her mess, it feels spot on as to how you might overdo it a little in order to cover immense hate or dislike for a person who is your captor. Once he sees what Annie is about, or notes her triggers, he tries to sidestep or become avoidant, rather than to keep marching through them, but he's a perfectly imperfect at this and because Annie is imperfectly unbalanced (as obviously played to the absolute hilt by Kathy Bates) even when he's not trying he still accidentally lands on a mine which makes it believable. Around the third act Paul begins to hide away the pills that he suspects that she is drugging him, smart but not too “No Way” smart. He later sends her off on an errand to get the exact type of paper he loves, ( I’m still not sure whether this was a lie or thinking on his feet because it all fits in with what we have previously been told about Paul's very detail-oriented routine ) Annie has been so eager to please as it concerns his writing process this seems brilliant and infallible, and yet it it sets off one of Annie’s mines leaving an unsuspecting Paul with one of those “Necronomicon”thick books dropped on his still very tender legs. This is another vital aspect of the tension set up. Annie’s hair trigger emotional status. It is setup very early, that things that set Annie off don’t have to be connected to any theme. Its not the horror or thriller protagonist where if you tell them you’re not scared, or talk shit about their mama you’re going to get a reaction. Annie might get mad about cursing, or the appropriate name for trailers, it’s very much like being in an abusive relationship. All of this sets up maybe the most tension oriented scene in the film where a bobby pin that Caan's Paul has stowed away (again thinking on his feet) is now used to open the door so that he can somewhat explore the house and see if he can find himself some sort of defense against this woman or call out for help. The lengths that Annie has gone to make sure that no one can interfere with her plans, become even more evident here and we see how well thought out this was. As Paul's options are lessened so are ours. Then we are also introduced to a sort of “ticking clock” scenario where we know that Paul has a limited time do this, by way of cuts to show us exactly where Annie is at on her trip. The fact that he is disabled is not merely for effect, but it does have an effect as an obstacle to help intensify the tension in our minds due to the fact that we know any place he goes into this house its going to be hard for him to get back to that room in time if Annie shows up, (especially if he doesn't hear her) that is intensified to yet another level when his wheelchair can no longer fit through the door and we see that he now has to get up out of his chair and crawl over to pick himself up a knife, and at the exact time, the moment he secures it, we hear a car pull up and I wish I would have been in the theater to see this because I would have gathered that there might have been a collective gasp in the theater the moment those wheels were tracking up and we come to see Annie now getting out of the car knowing that this man has to get back in that chair and move all the way back to that room. I've seen that movie a million times and it still causes my heart the climb ladder 49 straight up into my throat every time I see it.

The power of Misery, the part of that dances up and down all over my nerves as a horror movie as well as a thriller, is the way it narrows the walls, gates, roads until the only way out is through. Paul being a clever protagonist who tries to outsmart Annie and eventually realizes he just has to play through her game, makes it so we don’t get to feel safe by knowing we have the answer to his freedom. Most things we might’ve thought of or considered he did, and beyond. We are left with only the face off. Who will come out? We don’t know til the end, and it’s an end that comes by way of a lot of suffering, that comes by way of nothing else but what some may refer too as just plain bad luck. If there was an insurance claim on Misery's type of horror almost none of us are covered, it’s an “Act of God”, and I always hate those. It’s why avoid this movie, and fall in love every time I watch it, it’s that horrifying to me, and its that good.

FORGOTTEN GEMS: 1995’s “BAD COMPANY”

/Three things come to mind watching Bad Company Laurence Fishburne, Ellen Barkin, and style. In many other cases , for other films this would not be a good sign, it would be a weakness, here it most certainly meant as a compliment. Bad Company carries itself through its less than two hour run time on the near visible steam wafting off its two leads, its warm summer cool, and rapid fire dialogue delivered with the kind of sterilized precision one might see in an operating room..a very stylised, and well decorated operated room, where the doctor plays Jazz to set the proper mood for his work. The movie introduces us to Nelson Crowe (Fishburne) a CIA man disavowed by the agency under a cloud of suspicion. It s precisely what got him ousted from that agency that interest Vic Grimes the creator of a corrupt firm that offers it's services in corporate espionage to the highest bidder. Grimes number two is Margaret Wells (Barkin) who instantly takes to Grimes and has other machinations of her own. What ensues is a deadly game of Cat, Mouse, and Bigger Cat in a room full of rocking chairs. The movie in some regard is a bit too detached, disavowing any real vulnerable emotion in a vacuum tight seal of unflappability, but man is it fun to watch it's two stars skulk, slither, circle, and screw each other. Denzel got all the press, attention, and adulation during the 90's , but while Washington is and was certainly his own category, so too was one Laurence Fishburne. For a guy who had carved out iconic roles in films like “Boyz n the Hood”, “Deep Cover”, and eventually What's Love Got to do with it, and “The Matrix”, Fishburne does not seem to conjure the same sort of magical recognition that Denzel's name does. Watching this movie, I was reminded of the sheer heights and depths of Fishburne’s sexiness, his charisma, his singular ability to give you a whole mood with a very simple non-descript action. Watch Laurence Fishburne sit on a couch..

Stand in an Elevator…

Admire Ellen Barkin 's leg..

Doesn't matter what it is Fishburne is doing, he is oozing self contained composure. His dialogue is terse and concise, and he imbues it with exactly the kind of direct efficacy and command needed. His enunciation is as close to perfect as one might get, and it is not simply for his own benefit as an actor. He performs the task of aiding in the creation of this near inscrutable character. It's tempting to say Fishburne carries the film alone, he's magnetic and charming enough to have been able to, but fortunately for all of us Ellen Barkin is also in this movie, and she is also quite able to carry the film. This is the equivalent of having LeBron James, and Anthony Davis, or better yet the big three in Boston seeing as though Frank Langella and a host of natural character actors like Michael Beach, Gia Carides, Spalding Gray, and Daniel Hugh Kelly fill out the rest of the cast wonderfully.

Barkin is a sneering, smirking, glaring force of nature. She is like pretty much everyone in the film ruthless, calculating and acting wise she is divine. She is both threatening, and supremely attractive, not just attractive in the sense that she looks good (tho she does) but as in the pure quality of attracting others, it’s easy to believe that despite what she is, people want to be in love with her, and around her. When she's not a cat, she's , snake, when not a snake, she's a lion. There's always something brewing under her eyes. Something deadly, but undeniably distant, and yet close, and there is a confidence and swagger that is the perfect compliment to Fishburne. Her character Margaret Wells never says as much , but it is clear from what Barkin gives us, Wells feels cheated, passed over, and deserving of all the things men around her have denied her, or refused to acknowledge on a full level in her. She walks around like she owns the place because she fully believes she can and should, and nothing the audience is shown nothing that proves otherwise. Barkin provides maybe the film's two best acting moments in the movie with neither featuring a single word. The first when the reality of a misdeed comes crashing down on her. We know this because Barkins face tells us in a muted, layered, complex, and compelling reaction that ends with a crooked smile that hints at both her devastation, and her determination.

The other comes when just as Wells seems to have gotten what she wanted, but before she can even settle into achievement of her life long pursuit, she is hit with the news she is in fact under the thumb of yet another man. Barkin’s reaction is indicative of everything she set up from the beginning. She grates underneath her skin, her chin goes down, she inhales deeply, and her eyes nearly burn a hole in the table. A beat…She then composes herself, and looks forward. Barely containing her anger, but containing it nonetheless, she swallows the ash, and then.

Barkin and Fishburne's chemistry and skill permeate, and elevate this movie, but they or the rest it's top-notch cast are far from its sole delight. Director Damian Harris (son of actor Richard Harris) punctuates his actors performances with the films stylized aesthetic, pace, and imagery. The movie is dark, and it settles but is rarely still. It broods, but the color palette, lighting and pacing make it pop. The mood and tone is cynical and straight forward but delightfully off color and funny . The movie is the rare 90’s political thriller that doesn't feature a good guy, or slink away from its own amoral world building. It's has a bevy of wonderful characterizations, and is wonderfully diverse without being heavy handed or forced. There's a black man, and a white woman, who while the movie never overtly speaks to the precarious nature of their identities within that world, it is nonetheless present and implied especially in the case of Barkin. Two gay males (one Black one White) in Hugh Kelly's Les, and Michael Beach's Tod Stapp. The parts are not thorough explorations of the interiority of their lives, but truthfully no one in this movie is. Though Michael Beach’s Stapp is especially derided and berated based purely on his sexual orientation by homophobic superiors, (and Im on the fence as to whether thats realistic or unnecessary and also realistic) the movie itself does nothing to support the characterization, and gives him a full voice. It doesn't sanctify of martyr him or Les, nor does it condense them. They are as amoral, conniving, and detached as almost anyone else in the movie, and they are definitely as cool. They survive the entire film, and Beach gets the last word over his former employers. Gia Carides's “Julie Ames” would in another film be a banal trope about gold diggers, but here though obviously no saint, (sleeping with a married man) she is what comes closest to the movies morality. She doesn't want the bribe offered to her lover, and her relationship with him isn't downplayed to justify the actions of our antagonists in protagonists clothing. it's a real and flawed relationship in a movie about a spectrum of people that goes from deeply flawed to detestable. This is what l love most about Bad Company. It lives up unapologetically to its title. The movie is as detached from emotion as its characters are from morality, but with its moral compass still attached. It is a moral film that isn't righteous. This den of immorality is cool, and sexy, and slick, but it is never once enviable or desirable in the sense that you want to be around these people for any prolonged amount of time. These are death dealers, cruel nasty, and despicable folk that use sex, charm, and deceit as currency. The film isn't interested in whether they deserve their fates as much as it is the natural progression towards them. It's exactly what you expect out of a political thriller, and some of what you don't. Sexy, smart, twisty, and sharp, and revolting at the same time. A showcase for the talents of its ensemble, and the best of political noir that deserves a revisiting.

"Gotta Be Who You Are in This World: The One Scene in "The Irishman" that REALLY Struck Me

/Martin Scorcese’s “The Irishman” feels like a movie whose full value won’t be able to be ascertained until a few years from its actual release. Maybe one of those films in a directors catalogue which may grow a following, or lose it, after the years allow revisitation from fresh eyes, and new minds by a new generation. Upon my first viewing it felt about 45 mins too long, and nowhere near as memorable as past efforts by the famed director. The dialogue didn’t have the crackle that former films did, the direction didn’t have the fury, and the roles though still quite skillfully acted felt all too familiar. As a meditation on growing old, and the passage of time and death, it felt tepid, and lacking in revelation. Ive heard about these people before, I’ve seen notes on the fragility of life, and the whisper of death, and without saying anything I could cling to that provides a fresh perspective beyond Scorcese’s own catalogue, I was only moved in starts and fits. Nevertheless as an actor, and as an audience member, there were a couple of scenes really hit me in Scorcese's latest, some involved the still lacking storyline with Sheeran’s (Robert DeNiro) daughter (Ana Paquin), the other was a punch in the gut scene involving Pesci asking Sheeran to commit a crushing betrayal, but but no scene more-so than one that took place about three quarters of the way through the film. At this point Pacino’s Hoffa is beginning to come undone. In a fascinating combination of righteous indignation, unflappable principality, and enormous ego, he refuses to heed the man-made winds of change. Told time and time again he’s walking upon very thin ice under which murderous intent lies, he refuses to walk even a shade lighter. It’s the kind of behavior that infuriates audience members, and characters alike, (though we rarely ask why?). For me it was partly because of my affinity for the character. Recognizing Hoffa’s stubborn resistance as not only the preamble of death , or the most glaring flaw of the character to someone who in fact now wants him to live despite his egregious sins, but also as the inevitability of time and the futility of resistance to its grip that applies to us all. It is a bit of Spinoza’s determinism, where the necessity of our nature brings about the self actualization, or in this case manifestation of our our own fate. what was going to happen was always going to happen by way of our own distinctive nature. The scene in question takes place in a commemorative event for Robert DeNiro’s Frank Sheeran. He invites Hoffa (Pacino) there out of sincere love and fealty for a man he feels mentored him in some way, but as tensions build between Hoffa and the Mafia - Sheeran (himself involved in organized crime) along with Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci as good as ever) are left to play peacemakers. When Bufalino’s attempt to corral Hoffa fails miserably, Sheeran attempts one last time to get Hoffa to fall in line. When innuendo doesn’t work Sheeran makes it clear that Hoffa’s life itself will be the price… Pacino's reaction is the ultimate encapsulation of Spinoza’s determinism .

When Pacino looks into another direction its almost as if he looks into the abyss and peers into his fate as he says “They wouldn’t dare”. There's a bit of recognition there. Pacino’s eyes betray a profound sense of conflict. A small battle that lasts all of a few milliseconds before the skirmish is concluded and one side is declared the winner. The side that was always going to win, the side of him that knows him best, his nature. In that one moment is a bit of fear, doubt and then a realization "I know , but what can you do?" There's sadness, and a tragic resolve, and as frustrated as it may have made me, it was principled, and subsequently it is both honorable , and foolhardy. The intersection of frustration, inevitability, and rebellion, and recklessness in Pacino’s reaction is transmitted from actor the scene to viewer like a cold. Where our planes meet is in our own inescapable slavery to our compunctions, wills, and ultimate make -up, with respect to very specific deviations, we are who we are, and the mutual realization of that is the power of the scene and of Pacino’s deeply stratified performance. It is one of the few moments for me, where actors, writer, director, even lighting converge and intertwine conspiring to elevate the film to the peak of its lofty intentions, and it’s also a heartbreaking portrayal of how the best of ourselves is often also our worst even as a audience members.

Donnie Brasco: The Gangster Film You Needed.

/If you were to ask me to make a list of the all time greatest gangster films I'd run off The Godfather pt II, Goodfellas, The Public Enemy, and Donnie Brasco. Mike Newell's film - based on the true story of FBI agent Joe Pistone's infiltration of the Bonnano mafia family , under the alias of Donnie Brasco - doubles as one of the great undercover films largely because of its nuanced look at what the work would do to anyone, and because it features one of Johnny Depps finest performances as said undercover agent. But while I think what it has to say about that particular work has been said or done before in films like The Departed, and Deep Cover. What it has to say about life in organized crime, how it depicts that life, is something we hadn't really seen before, and not much after. I may actually watch other films of the genre more ( Scarface, White Heat, Casino, and of course two of the three Godfather's) but while I don't watch it as much as those films, I feel very passionately that what Brasco manages to do that almost no other gangster film has done this well, is make these people, this life seem completely unattractive (which is saying a lot considering how handsome Johnny Depp is in it). It doesn't normalize the racism, violence, and paranoia, it makes it look very normie, cumbersome, mediocre. It doesn't have any of the feel of a winning formula (even if for a time) one can siphon off from other films in the genre. This not to say its the mission of those films to do so, but rather there is something to say in talking about the place characters like Vito, Michael, Sam Rothstein, Tony Montana, and Tommy DeVito have occupied in hyper-masculine circles ( such as Hip Hop). If the gangster film (intentionally or not) made the environment and people look like a 300 dollar pair of slacks, Donnie Brasco puts them in “Dad” jeans. Crews and bosses seem petty, tacky and cheap. Prone to bouts of furious delusions of grandeur they stomp about town carrying out heinous acts for no other reason than percieved disrespect. This about actual disparaging, or defamatory remarks made over a shoe shine job when one was a kid. In one scene Donnie, (Johnny Depp) Sonny Black, (Michael Madsen) and his gang viciously beat up an Asian restaurant employee merely doing his job in a bathroom and it's not the cooled honorific hate in other gangster movies where they say things like “Give the drugs to the niggers their animals anyway” which is more distant, and less visceral, and mostly about them and their staunch belief in their own supposedly superior ethics than their hatred, - it's a messy, cruel, up close hot blooded bit of nasty raw racism that a cop uses to get out of being found out because even though he doesn't know to what degree, he knows it's the button to press to get the desired effect.

The violence and the politics are made to look messy, to look like hard work, to look like stress, because, (along with the also underrated Road to Perdition), Donnie Brasco is a gangster film for and about the working class, that remains about the working class. While it's counterparts are significantly about an expressway out of the blue collar life. It is not the cops and robbers film that is The Untouchables. Pistone is not Elliot Ness, a straight laced do- gooder dedicated to his job out of a moral superiority (for that matter neither was the actual Ness). Director Mike Newell’s film is neither a total indictment of the path, nor a rousing accidental exaltation of gangsterdom, merely a stern, gripping, stare into the bare face of that life, and it all starts with it's penetrative look at it's central character Lefty Ruggiero.

Ruggiero is a bit of everything to this film. He is it's conscious. It's reckoning, it's soul. Lefty is not only undercover Detective Joe Pistone’s way into the heart of the mafia, but our way into the heart of the movies central themes. Understanding what makes Lefty different from anything else we've seen from a crime syndicate figure on film is key to understanding why the film is different from anything we've seen in crime syndicate films. Up until this movie, the American gangster on film is one of the purest of white American male fantasies on screen. Although they were usually anti-establishment, anti- authority figures, the gangster would still none-the-less be the flip side of a mirror image of the establishment hard-working American who rises to the top by way of ethics, attitude, ingenuity, and talent. That they functioned outside the purview of the law did little to disrupt the institutional philosophy, it just made them a whole lot more interesting, and desirable. Up until Donnie Brasco these men we're presented largely as reliable narrators of their own rise to power. How they saw themselves was exactly in essence how we were going to see them. They were men of indomitable wills, they were tough, intelligent, and ladies men. They lived lavishly from goon to kingpin and along their rise to power came to enjoy the best of things. Though all of the great films of the genre would also interrogate the underside of the fantasy, they would also engage in portions of it. The Scarface movies showcased their lust for power, Godfather romanticized their codes of honor, Goodfellas the brotherhood. They were all tragic figures, but the tragedy was the fall of the empire, or that none of it was ever real in the first place. Then comes Lefty Ruggiero, and Brasco where the tragedy is futility, of these men's lives, of Donnie Brasco's work. All of this to get out of a lifestyle (working class) that for the most part they are still in. There is no rise to power for Lefty, his gang, or his protege in Brasco. No honor or true sense of brotherhood amongst these theives. They are all willing to berate, betray or kill one another for a dream which will never be realized for any of them. Their lust for power is not attractive, or ambitious, but ugly and small. It is not a story of rise and fall by way of strength and weakness, but simply an ongoing tale of mediocrity and ruin, and Lefty is at the center of all of it. There are no tailored three piece suits, and gorgeous lapels and colors as in Casino, but hideous track suits, and mismatch outerwear. There are no palatial villas, stately mansions, or even quaint track homes, merely small cramped apartments with tacky furniture. Lefty is not an avatar for white alpha male potency and supremacy, but the sad sack reality of an average moe scraping and scratching for a seat at the table. He is a hypochondriac, and a liar, not particularly smart or ingenous, and prone to overstating his importance. He is also a loving father, an at least a decent husband, and a loyal friend, not as an act but as a character trait. It's maybe Pacino's most sympathetic and pathetic role since Panic in Needle Park and Dog Day Afternoon. There's his patent sadness round the eyes, less posture, but always posturing. There is a scene maybe Midway through the film that exemplifies all of this where Lefty is in the hospital anxiously awaiting word on the condition of his son, an addict who has OD'd. As Lefty begins to emote just a little over his son, he begins to show sincere signs of guilt, of recognition, of vulnerability, and you can tell his son is a source of deep pain for Lefty but you don't know exactly how much until suddenly, Pacino lets out this gut wrenching whimper. It’s not long and he immediately composes himself, but it's a level of being right there in that exact place, in that exact emotion that has a degree of difficulty for an actor on the same level as Denzel's single tear in Glory, and it's indicative of the kind of lived in acting Pacino commits to the entire movie.

Pacino plays Lefty as a small man, with a bigger heart than he lets on. A character with traits that resemble a loyal dog with a mixture of bite and bark, who chooses to bark more than bite. One who doesn't have much heft, but likes to throw his weight around, and Pacino makes it a literal part of physicality. He tosses weight from one side of his body to the other while walking, and talking. His constant anxiety is transmitted into Pacino's many repetitions. Chain smoking cigarettes, appearing ready to ash a cigarette, but returning to his mouth as if by compulsion. Repeating words and sentences, rhetorical questions repeated at least twice. A quarter turn in the hospital hallway directly followed by another. A longing look to the boss for some form of acknowledgement, directly followed by another, like someone checking the mailbox twice for that important piece of mail they've been waiting on...

Ultimately what becomes vital to understanding Pacino's Ruggiero is nothing other than existing in the current state of perpetual unease in the American economy. Lefty is not a trumped up , souped up Lamborghini version of a champagne drenched masculine fairy tale. He's the Toyota Camry and stale beer reality. He's a hump, who all his life carried other peoples water in hopes that one day he'd be swimming in his own pool, looking into his own mansion filled with people that respect and revere him as the top dawg. He blinked and it was twilight, and there he was relatively in the same place he began. All the death all the lies, the hard, herd work, and the indoctrination for what? There is a scene later in the movie where he and Donnie are in the car discussing the death of Nicky (Bruno Kirby) a former associate and friend whom Lefty murdered with the okay of his boss over a completely unconfirmed suspicion. In yet another bit of astoundingly layered acting by Pacino we watch the doubt, realization, creep into his conscious, break down his defenses, and set the timer for implosion of his whole life, plunging into chaos, right before he cuts the blue wire and returns to his ordered world.

The tragedy of Donnie Brasco and Lefty Ruggiero, is that they are both acutely aware that they are just spokes on a wheel, and that both of them want out , but are held prisoner by their own convictions, and belief in the systems they perform from within. They believe them because they can't afford not to. In a physical sense, but even moreso a psychological. If the fantasy, the dream of each of their piece of America isn't real , then what is it all for? The alternative is far too depressing, far too morose, and it's both part of the films power, and what makes it a hard watch. The film credits roll, and though Donnie Brasco isn't beguiling us, it isn't selling us, it ain't even preaching to us, it feels punishing merely existing in its “too close for comfort” realm of plainness. A somber meditation on loyalty, code, and the illusory nature of the American dream , where it's protagonist is no hero, and it's antagonist no villain, nor the reverse. They're merely humps carrying the load of other people's success to and from them on their way to their own fates, much like the rest of us. What this makes Donnie Brasco in effect is almost repellent. The movie bucks a long-standing understanding of what audiences are supposed to expect from the genre by creating a film that is less a movie about ascension, than detention. The movie is not the realization of potential, but the holding back of by various external forces and self impediment. Lefty Ruggiero is not a manifestation of a particular desire in us for affirmation of our mobility in the increasingly narrow margins of society, but a confirmation of our worst fears, that it may all be for naught. The movie is in a state of flux, of anxiety, and unease about it's characters, their relationships, and ultimately the ending. What is Pistone doing this for? Putting himself through this for? Lefty's lies, cause Pistone to consider his own. Lefty's sins his own. Pistone's minor rebellions and revolts against upper management are not merely a matter of the undercover work wearing on him, but the image of himself and his job becoming more and more visible for what it is. Lefty and Joe are both on the same journey of existential, saddening self discovery, and it makes their friendship one of poetic melancholy , and the movie an ice cold slap of water to the face in the midst of a deep sleep. It is an enjoyable, quotable, and sometimes even funny movie, but also the sobering reality of what it feels like to be a gangster in a world where missteps very likely mean death, and in that light is not the gangster film we wanted, but the gangster film we needed.

Joker: "The Killing Joke"

/I went into Joker admittedly wary of the entire “controversy” around Todd Phillip's film. The whole thing seemed sensationalized as a ploy to create a weighty buzz around the film that would make it as close as possible to can’t miss box office. To a great extent I still believe that, but before I actually watched the film I genuinely had no idea what to expect going in. Did any of what I had read have any validity? Was the movie a rallying cry for incels? Or was it a brilliant misunderstood movie, with a message too unsettling to be heard just yet? Having now seen it, I have been converted (somewhat) to the group of critics who find the movies messaging to be problematic, though I’m still not sure future viewings might unveil the latter. I had to let the movie sit with me awhile, talk it over with family members before I discovered what it was that made the movie it so hard for me to just give the movie the unencumbered praise I was clearly ready to give Joaquin Phoenix’s performance. Ultimately I was reminded of a Dave Chapelle sketch, and something he said during the intro. Just before he begins the wildly outrageous "Dave Chapelle Story” I remember Chapelle remarking he would be afraid to write his own story because in essence he would be an unreliable narrator, and the temptation to embellish would be too great, and I found exactly in that moment what had been bothering me. In essence this was the almost inevitable folly of telling a story almost completely from the Joker's point of view. The movie wasn’t just unsettling because it took on the hard task of asking us to empathize with, and weigh the contributing factors to a murderous malcontent, it was unsettling because there was an invaluable piece missing from the execution of said task that invited an audience to not only empathize with the facts of what and who society marginalizes, or the nature of loneliness and outsidership, but to empathize with the fabrications and extremities of the Joker's behavior. What the movie did well was forcefully connect us to a person none of us wishes to be connected to through the universally recognizable devastation and frustration of being unseen, unheard, and unable to connect. What the movie omits is the line between us and him, by way of a nebulous, muddy line between what is real in the movie , and what is in the Joker's head. One could claim that many of the events that happen in the movie (it being told from the Joker’s own violently delusional point of view) are delusions, one major storyline is clearly revealed as just that, but therein lies the rub. You can make a movie like Inception and be unclear in the end about whether the whole thing is just a continuous dream , because at the end whether or not Cobb is choosing to live within his own self delusion really only effects Cobb. Being willfully ambiguous about the Joker's delusions effects the world around him and subsequently invites the audience to endear itself to a character who in no way is a hero or a reliable narrator. If you show people lionizing the Joker at the end of a movie, and the audience is left unsure as to whether he was really carted straight to the station or whether the city turned upside down as the result of a revolution started by a psychopath, (and especially if you’re saying that it happened exactly that way as a result of the superficial connection between the Joker and the rest of functioning society) you're (in the strictest sense of these words) not doing it right.

I could go on illustrating what struck me as problematic about the framing, and what I think they got wrong, but I always prefer the approach of illustrating a misstep by showing what it looks like when it’s done right. Another memorable cinematic character The Joker has a lot in common with is Anton Chigur from the Cohen brothers masterpiece "No Country for Old Men". These are two men who metaphorically represent a sort of apocalypse, an end to things as we know it. They are chilling, intimidating and unnerving precisely because they have psychopathic tendencies that can't be reigned in or anticipated by any consensus on logic or reason, because they live in a world so far outside the constraints and constructs of society, they function a lot more as a force rather than an being. They have their own sense of rules and extremely unique coding, and they're only predictability is that they are unpredictable. If you listen to other characters discuss them, you can see the bridge in the similar way in which they are described, and the complimentary construction in the similar way in which they discuss their disdain for "rules" in these two scenes. First the description of each by ancillary characters ...

And then in their own voice on rules...

Though the Joker in the Dark Knight is clearly a different approach, it’s not entirely different, just more removed than this film, and the point I'm setting up is that though these characters are clearly very similar, one movie (Two if you include the Dark Knight) understands it's character (Chigur) and lives in the truth of the character, so that it is impossible to associate in any way Anton with righteousness, or justice. Anton makes his decisions in a way that cannot be found appealing, or imaginable, the discomfort we feel when he is around is from the injection of chaos that the film continuously honors. The Joker on the other hand, has very little integrity regarding the chaotic frequency the Joker lives on. Phoenix’s performance provides the consistent element of surprise, but for all intensive purposes the movie functions with the straightforward A to B arc of a superhero movie. A linear set of happenings congregate and aggregate to help form and create what we will come to know as the Joker. The film plays fast and loose with the reality of what someone of that disposition would act like to make a more sympathetic character under the ideologically fair stance that these people aren't just born they are also made, but without confronting the things that bring about the extremes in their behavior. Forget his glaring whiteness in this very multicultural world, what about his narcissism? The movie makes out as if DeNiro’s late night host is an unnecessarily cruel dream crusher because it never disengages us from the Joker’s perspective. It never confronts in any meaningful way the facts that Arthur is in fact adamant about his ability to do something he is clearly not talented in, that he skips steps, and more importantly doesn’t even like it. This is not Tommy Wiseau, this is (as the movie’s own creators told us time and time again) Travis Bickle. His stalking of a woman is not played for it’s terrifying truth, we get none of the existential dread we got watching Chigur stalk victims because we see it only from the Jokers perspective. Zazie Beetz is never truly allowed to be a full being, to challenge for reasons that also have to do with plot device. The movie (Intentionally or not) continues on this way, skipping, dancing, laughing well past the line of superficial connection between the audience, society at large in the film, and the Joker, to one that would have us believe this is just a broken men just like one of us, just pushed a little further. It is disingenuous, and a dismal fabrication, indeed typical of someone like the Joker, but one that should have been better addressed during the actual film. Many of us believe we have been shoved to the margins to the point we might break, many of us fight back. Many of us deal with mental health, and those that deal with the deeper more difficult forms also know how society at large seems to care very little about listening to those who do, but most people dealing with either or both don’t go off and commit a trail of heinous crimes. There is a difference between the Joker and marginalized people, the movie (in the name of telling a story true to the nature of the Joker’s identity) just isn’t interested in drawing any. The danger of this position is not that it would invite or incite others to commit similar crimes under the guise of victimhood, but that it backs their claims without any formidable counterbalance. This is why I'm not sure of the efficacy of, and find myself baffled by the somewhat new trend of telling stories completely from the villains point of view. On it's face it's an absurd approach , and if it's not approached in the spirit of that absurdity, with other characters with some version of significant roles to bounce the signal off and echo back the true essence sound and meaning of their reprehensible actions then it becomes too easy to mistake their spoiled fruit as food for thought.

I think it's okay and even important to sympathize with the social incongruities that make or mold the Joker, or any terrible human being fictional or otherwise, maybe even his/their rage, but when his actions can at all be taken for righteous retribution?

As a vehicle for an actor (especially one of Joaquins talents) Joker is once in a lifetime. It's an intriguing idea that maybe works better as a one man show on Broadway, but as a film? It's far too isolated, and to make things worse, the better the performance the more likely it is that the audience is going to empathize, and sympathize with the narrative that drives him. Villains need heroes as a counterbalance to call them on their bullshit as much if not much more than heroes need villains to reflect on theirs. If not heroes in the sense of meta humans, or insanely rich but complex men or women, then in the type of heroism, and courage exhibited in a humble but straight-talking and intelligent wife like Kelly MacDonald's Karla Jean in “No Country for Old Men”. Or in long suffering sons like Russell Harvard's grown up H.W. Plainview in "There Will Be Blood", hell even another villain like Paul Dano's Eli Sunday can be a potent mirror from which evil can reflect and be reflected upon by the audience. But Phillip's Joker has none of these . None of which could be reliable because the movie is told so singularly from his perspective. So that if he says he let a person go because "They were always nice to him", or that he didn't murder his next door neighbor, or that a black woman rather unnecessarily and more to the point unbelievably told him to stop playing with her child on the bus , we are at the very least asked to believe it's plausible that these things actually happened, because there is no one to challenge any of it who doesn't have their own challenge rebuffed by their own membership in the very system the movie has compelled the audience to take umbrage with. This is not moral complexity it's negligence. If one were looking for what moral complexity should look like on film as well as the need for counterbalances, this scene from David Fincher's "Seven". would be a fine example..

The scene begins with the question "Who are you really?" setting up the psychological impetus of the scene as a complex unraveling of who John Doe is. The scene is full of moral complexity, but John Doe is not going to get to tell his story unchallenged. While we may sympathize with some things John says, and even a few of his attitudes, the counterbalance of both Pitt' straightforward assessment and especially Morgan Freeman's acute observations ensure it's impossible to leave that theater feeling anything but that this guy is the absolute worst. He's impotent, fragile, weak, and pathetic, a tragic figure in some sense yes , but nonetheless gross. Thinking of the difference in these films and their effect , or rather the effectiveness of their portrayals I'm reminded of one of Sommerset's observations in Seven...

“If you were chosen, that is by a higher power. If your hand was forced, seems strange to me that you would get such enjoyment out of it. You enjoyed torturing those people, this doesn’t seem in keeping with martyrdom” - Sommerset (Morgan Freeman) in Seven”

Within the context of the film this is the actual unmasking of John Doe, and of Phillip’s film. It's the equivalent of the Scooby Doo teens pulling the the hood off of the episodes perpetrator. From that point on all illusions are put aside and the villain explains exactly who he is, and the audience sees him for exactly what he is, not what he wishes us to see. Sommerset in that way has also provides us with a revelation that we never really get to see or hear in the Joker which is that this is not some martyr who kills only out of furious passion those who have wronged him. His targets conveniently all disagreeable, and unsympathetic bullies, this is a killer, a megalomaniac with delusions of grandeur, and that should've been the the ultimate resolution of Joker . It should've ended with him confronting that reality, and maybe then evading it as in Nolan's Memento - not with him being lionized in the midst of a revolution followed by him running through the Halls of an asylum after an allusion to him possibly killing a worker in an interview. I for one absolutely believe you can make movies about psychopaths, and killers, and all sorts of villainy. Mary Harron made one of the best ever in American Psycho with it's unabashedly scornful portrait of materialism, and greed as psychopathy, that embraces the very absurdity of its position as aforementioned, BUT you can't make movies ABOUT psychopaths if you catch my drift. If you don't make clear the actual motivations behind this kind of extreme behavior beyond Mental health, and victimization, then your setting up the stigmatizing of one group , and the validation of bullies and tyrants. Though I don’t know this makes The Joker a bad film, - despite my feelings about it's messaging I actually think driven by Joaquin's performance, and a long overdue interrogation of our framework around Batman and his family it's a pretty damn good movie, - but it does make the controversy and the debate around this film real , and deserved. The Joker gets to tell his own deranged story without interruption, or opposition to an audience willing and ready to listen, and while movies don't make us do anything , they do often color, inform, and help crystallize our philosophies, or ideological views. Given that realization it makes clear the responsibility of the filmmaker to tell stories that don't back ideologies that will help convince already lost, confused, and possibly deranged audience members of their own righteousness, and even if Joker doesn't necessarily defend a skewered perspective, it doesn't upend it either. Subjectivity is a killing joke in the context of heinous criminality, not in any corporeal sense as it relates to film, but in the essence of the moral drive of your film. You can make Bad Lieutenant, but not subjectively contemptible Bad Lieutenant, there is no place for subjectivity, or a lack of clarity in contempt around heinous acts of wanton violence, not in real life or on film.

The Disappearance of Diahann Carroll

/Its crazy because when I heard, or rather read and then heard, because the words became so deafeningly loud in my head - “Diahann Carroll has died” , My mind began instantly searching for something beyond the obligatory “Oh My God” you'd think..I'd think that as my mind turned over all my retrospective files on this woman’s career, I would immediately envision her sturdy brilliance in "Claudine" or maybe her part in one of my favorite dance numbers ever in Carmen Jones ( and that one eyebrow), let me not forget her role as Whitley’s mother Marion (in which she she basically played a version of Lynn Whitfield’s Matriarch that added her own unique flavor ) or her extremely memorable work in Robert Townsend's The Five Heartbeats playing a version of herself so committed she nearly tears through the silver screen in every scene…

But it wasn’t any of those roles that came to mind, in fact Diahann almost ceased to exist, and when I called for her in their stead, in her stead, the first image in my mind was of Elzora - Carroll’s small, but immensely effective and affective role in Kasi Lemmons " Eve's Bayou". Upon reflecting about it further it becomes easier for me to see why this stood out to me first. It’s soulful, its complex, its involves the best elements of transformation which are neither cheap or exploitive. Contextually Carroll's Witch is the underside of this black Haven. The embodied ghost of still disenfranchised members of families left behind or rolled over by privileged racist whites, and ambitious African-Americans who had the right amount of color, resolve, ruthlessness, or all of the above to climb out of their social dungeons. Physically Diahann Carroll brings revelation outside the margins of the scene, just as much as she does in scene. On one side she is Diahann Carroll Queen of elegance, unrivaled put togetherness, and “You Tried it” energy. On the netherside of that she is almost completely hidden by white make-up, strands of unkempt silver hair, and a mask of concrete surliness. Eve’s Bayou allows her to slink back into a side of her that largely went unexplored before it. She moves differently, as if each appendage has to cut though weighted space to get to where it's going. When you watch closely you see she has moments where she seems to have spells where she's lost herself, her bearings, her thoughts, and then she just returns. In this scene as well as later with Jurnee Smollet’s Eve, she is callous, but also warm, and Carroll turns it on and off in screen with such intuitive and adept understanding of when the one energy is needed over the other she creates an integral bit of mortar that glues the various bricks of southern life that form the gothic and loving house of memory and loss Lemmons built. Every choice she made in that film supported a comprehensive whole….

It’s a link to a forgotten figure in black communes, the wise woman or witch. Elzora is a tie to pre- christian practices of black peoples, and to the strength, power, and position these women held within those communities. What Carroll gives her is her sense of gravitas, and a regality, that belies a sense of past ancestral grandeur. What she sacrifices in the embers of this visually striking portrayal is the grandiosity that served as the inertia for so may of her other roles. It is this exact sacrifice of what powers your mega wattage as a star to the gods of thespians, that makes you more than just a star. Once you can make your Clark Kent every bit as powerful and resonant as your superman, well you’re in the most elite company of actors. This is why I love this role so much, it was so much in so little. It was an underdog role for an underdog character whom was made powerful both by the implicit nature of the script and by the explicit nature of Carroll’s performance. It was representative of all Carroll was capable of, of all she could do, of all many black women could do, but especially those with her raw and exceptional talents. She did just about everything you could do in an industry where so many do so little, if anything at all. She had an impact that couldn’t be argued, through it was sufficiently less than she deserved. In a way Carroll was the Queen that is both clearly in power, and yet under duress, and under-served, who is gone now resting in that very power. Extending her roots, raising the ground for future actors, (and black actresses especially) to stand toe to toe with their rightful peers.

Revisit: 1990's Close-Up, "You Can't Always Get What You Want"

/What is performance without cultivation, and curation of environment? What is life without the cultivation, and curation of environment? Can an actor be an actor without the help of an audience willing to go along with our minor deception? Abbas Kiarostami's “Close -Up” is exactly that, a minor deception, and a close up on a subject that seems small from a distance as was oft repeated and alluded to throughout the film, but a subject that when the focus was lessened and tightened revealed a great well of emotional depth, societal angst, and the very heart of filmmaking. Ali Sabzian is amongst the most interesting subjects ever placed in front of a camera. A seemingly simple character with seemingly simple motivations , who opens a wide range of philosophical questions about identity, and identification. A poetic soul who exemplifies a potent, and urgent truth about ability, and opportunity. Listening to him talk about the dilemma and difficulty he faced playing his idol Mohsen Makhmalbaf not in the abstract, but in crushing detail of his abject poverty I am reminded of the quote from "The Streisand Effect" episode of "Atlanta" where Donald Glover’s “Earn” poignantly says "Poor people don't have time for investments, because poor people are too busy trying not to be poor".

Alongside its stirring illustration of socio economic impediments, and disenfranchisement, it is what Ali Sabzian reveals about the nature of acting, as it relates to the cultivation of experience that permeates the relationship between actor and audience - that underscores the brilliance of this film. In the court scene which functions as the beating heart of this film, Ali points out that the family he deceived, helped provide the tools by which he, his performance, (and indeed the confidence in it) was developed, and encouraged. In essence, he points out that the more they believed, the more he too believed, demonstrating with humble but almost divine clarity the co-dependant relationship between audience and player, artist and patron, failure and success. Sabzian's words and story are also representative of both the reality and the over-simplified myth of meritocracy as a pure by-product of preparation and opportunity, when the truth belies a much more complex relationship. As Ali seizes his opportunity, his audience becomes vital to the success of his role and his scheme. Their belief is swelled by his passion, his dedication, his knowledge, and so Ali begins to leave the ground on the wind they provide beneath his wings, BUT as he does, the odds of successfully negotiating , and shirking all the well constructed social and aesthetic weights (appearance, finances, shame) that pave the way out of poverty weigh him back down, swallow him up, and spit him back out to where he began. Watching Ali’s story, it’s not hard to come by the conclusion that success (like a good caper) comes by way of a mutual deception similar to the premise put forth by the film “The Prestige” ( an audience willing to be deceived) , a confidence in that deception, and some well timed breaks . Ali fakes it, and he does it well because in a way he had been preparing for this his whole life. When an opportunity does present itself through happenstance, Ali didn't hesitate, he lept, almost involuntarily to take advantage, but it was only a matter of time considering all he didn't have. Ali’s lack of resources, and the limiting will of the players to provide a genuine opportunity. Once they discover what amounts to merely a label, a construct of Ali's identity, the play morphs from daring story of an ingenous, but desperate scheme to realize ones dream, to a ticking clock story set to eventually alarm the audience to deflate a promising balloon filled with human will and passion. After all disingenuous scheme that it was, as the director points out in court for all intensive purposes, Ali is an actor, if not a director. The only ingredients missing from a fully realized reality of his art are those out of Ali's control, the belief, of others, the finance. Every single production of art done through distribution is the result of a community of believers, and fellow role players who believe. Without them what your left with is what society might deem delusion, or even worse and more stigmatizing, poor mental health. What close-up reveals with it's penetrative gaze is the limitations of passion, ingenuity, hustle, and potential in society for any man or woman. The frustration of the impoverished artist is both the nearness and the distance of opportunity. It is the mirage of the oasis always just out of grasp. Sabzian can only have his dream for so long as the audience is willing to uphold his fantasy. He is a have -not, and while a few very fortunate players may "play" their way to success, it is largely inaccessible due to the constant molestation of chance, class, and in other situations sex, and race. In this is the tragedy of the play . The dreamers whose dreams are deferred, as much by his or their own failings as the many of society. The members of the Ahankhah family , who themselves struggle with the chasm between passion and opportunity (The Older brother is an engineer who ends up running a bread factory ) cannot abide his deception, nor believe his passions because they're pride is hurt by the fact that they ever believed in this man. He is a hustler to them, by their own estimation this is somehow vastly different from how a a “real director” would behave. There was a physical identity theft here, and yet it can be argued this is part of Ali's identity. Ali is both who he says he is and not who he says he is. No one including maybe even Kiarostami is willing to engage on any real level with the artist, to indulge him in his “play” a brechtian meta tragedy on identity and desire. In the end Ali is given some flowers, a bike ride, and a memory of just how close he came to realizing his potential. Close up, goes in to go out, and what it captures at the point of convergence is a paradox that breaks down the convenient conventions of unfettered access by way of will, and determination, for all his desire, his ingenuity, and willingness, Sabzian would end up hawking dvd’s in a subway station. And one has to find themselves asking why did no one give this man one opportunity, one chance to prove his worth. A production assistant, a tiny role, or even a scholarship? How far might he have have flown? Would he have crashed? I’m reminded of the great Rolling Stones song, You can’t always get what you want, but if you try SOMETIMES, you MIGHT find, you get what you need.

If I was to a curate of cinematic double feature of the themes at play I'd play Close -Up alongside Trading Places, a brilliant comedy that consecrates the philosophy that for a falsification of identity to become a reality, the advantaged must play along. Because the Dukes create and endorse the fantasy of Billy Ray Valentine it becomes reality, and once they decide to disengage the parameters and circumstances that affirm Billy Ray's natural talents , the play ceases until another fabrication and deception unseats them from their position. Ultimately Trading Places broadcasts a similar paradox, the fragility of identity, or identification. Both Valentine and the Duke's are in essence criminals, but the willingness of society to play along determines the difference in outcomes. These films through different lenses and focus, illuminate the illusory distance and proximity of success and accomplishment. Simply put these films masterfully remind us of the crucial aspect of all theater, a play is not a play without the willingness of both players, and audience to go along with the fantasy as described by those who have the means to create.

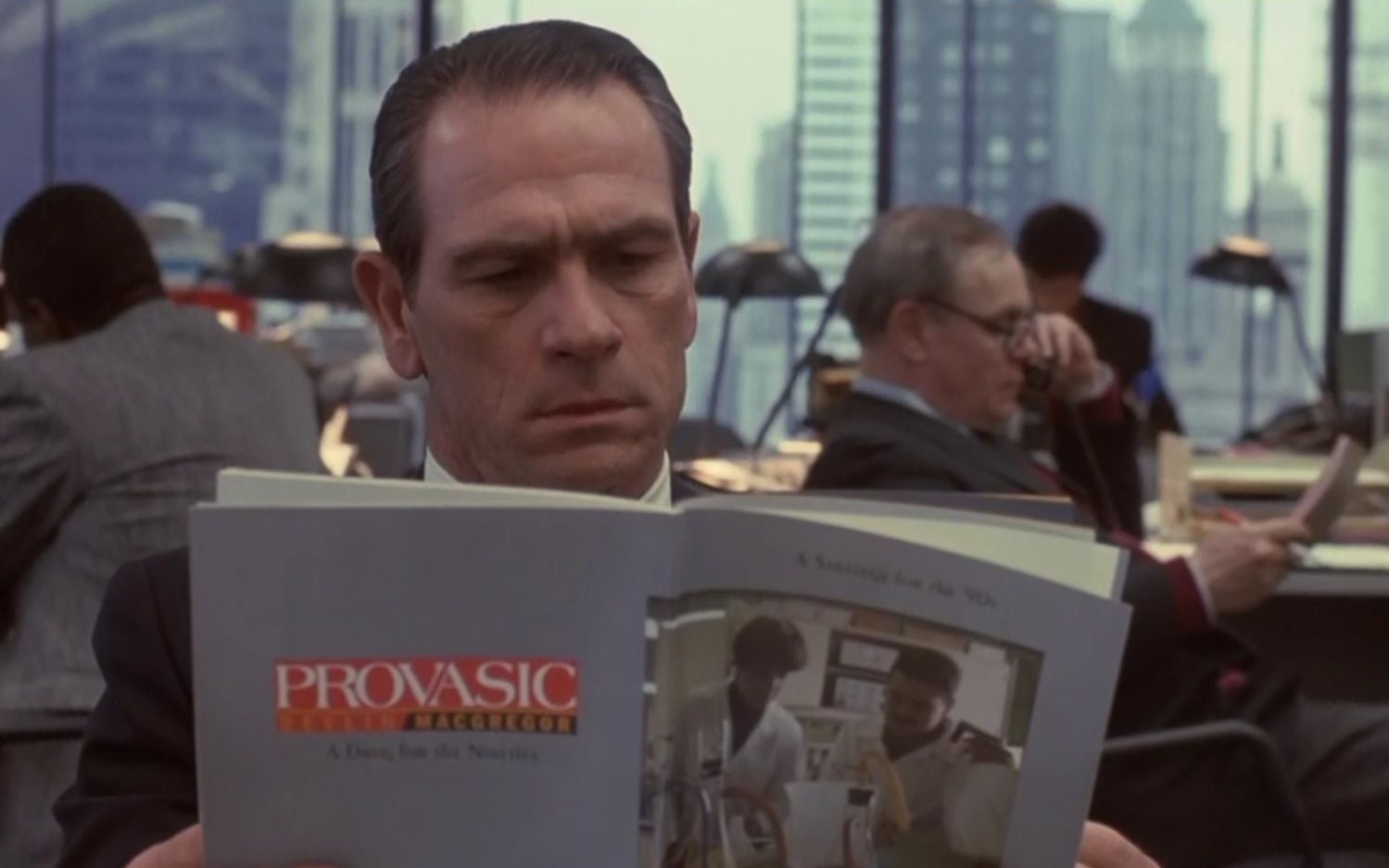

The enigma of 1993's "The Fugitive"

/What is the fugitive? It's not purely a thriller, though it’s not purely an action piece either. It’s not what you would typically label an intentional blockbuster, (though it did in fact become one) and despite its greatness it hasn’t procured the same kind of indelibility, or credibility amongst cinephiles the prestige of the sum of its parts (Like Tommy Lee Jones’s performance, or the presence of a great score from James Newton Howard ) might otherwise demand. ..

The Fugitive was accidentally ingeniously released in August of 1993. I say that because it’s release date, as well as its chosen director say alot about what the studios saw for this movie considering. August, that last month of summer usually carved out as a make shift parking lot for Hollywood clunkers and ne’er do well vehicles, gave it more than enough time to be free of the megaton fallout of Jurassic Park. Most viewers having sufficiently punched the ticket on somewhere between their third and fortieth viewings. Director Andrew Davis was a safe choice to lead such a film.. talented, but not TOO talented, tested but not yet cynical, the kind with ideas, but not ones so big they may potentially ruin your studios year. Having mastered the art of the slightly over mid-budgeted action film, in movies like Above the Law and Under Siege, Davis showed a soft touch with actors, a deft understanding of story, and a workman like precision. High expectations for this movie would’ve been in the 150 mil range, as mostly it was meant to be the kind of movie it came out with and would end up spawning ( a sort of middle tier thriller)…

1993 was somewhat of a beginning of the decade long obsession with mid budgeted thrillers with mega movie stars, of which The Fugitive is arguably the best of. 93’ saw Sidney Lumet’s stylish ode to Hitchock “Guilty as Sin”, Sydney Pollack’s The Firm, and “Malice” one of Aaron Sorkin’s earliest works on film.

The Fugitive’s ( and to be the fair The Firm also) influence on on the marketplace could be felt not only by the career paths of Jones and Ford in the 90’s (which seemed to be a decade long extension of these same two characters), but by the repetition of the formula - journeyman director, big stars, extremely similar budget around the thirty to forty million range. Some of these exact attributes function as contributors to what may have made The Fugitive disinteresting as a consistent topic of cinema. The film in certain ways wants to be a working class depiction of a city, an under the radar punch the clock film. One that celebrates it’s hard working denizen’s as well as its well-to-do. It features some explicit, and implicit commentary on corporate greed, and it has a diverse its cast, but this is all mostly superficial, as is any attempt at style or signature. The commentary is obvious, and lacks any teeth, never mind it being in short supply, the diversity is only in existence, (the characters of color have very little to say, and don’t particularly add anything to the movie besides background), and the final act of the this film doesn’t say much, doesn’t commit to much, and isn’t much to look at. Take for instance “Heat” Michael Mann’s cops and robbers masterpiece. There are similarities here…A dogged cop after his man, a final act that consists of the cop locating his man because he goes after the man who wronged him. They take place in very different cities , yet the goal is the same; that the city itself be a character in the film. And yet these two final scenes are worlds apart as it concerns truth, style, and power…

The Clarity of purpose, the lack of sound, save for the deafening screech of the planes, light and shadow, we are not telegraphed the ending, the playing field is even, the elements around the conceptualization of the scene see to that. Then there are choices, speeding up DeNiro’s death, the cuts, the close ups, the wide shots, and they all play integral parts to creating the tension. …

Here Davis telegraphs the ending as does the script, the placement and chosen order lets us no who is where. When you’re in a wide open field and some how it feels more precarious than a cramped laundry room its a problem of vision and execution. It not the location, its the choices that hamper the effectiveness of the scene. Nothing fits narratively, including why Jones character would go on like that knowing that the other guy is in the same room. It gives away his location,and puts him in unnecessary danger. It’s meant for us the audience to feel relief, which is the exact opposite of what we should be feeling , and its filmed the same way. The laundry scene would be infinitely more impactful, and nerve racking if each player moved in silence, letting the sound, and the feel of the laundry room be a background player, maybe even allowing Ford’s character who in actuality would be most likely to make such a mistake given how desperate he is to prove himself, give away his position by one way or another. The removal of the cuffs scene could be so much more powerful if it was the first time we find out Jones knows.

Nevertheless while its cinematic aspirations, and ambition, may be up for debate, and hard to pin down, that’s kind of part of its lasting charm. The Fugitive is almost artful in its ability to avoid any kind of conceit or big idea about itself. Its willingness to just let us the audience go on this noir-ish emotional thrill ride, with nothing other than the emotion tied to our collective insistence that this man be given justice as our propulsion is what gives it such power.. If it had any high concept as its bedding, it is of the power of pitting any one person(s) pushed to the brink will up against the will of the people, the city. The will of one man to make a profit, and another to bring about his own straightforward idea of justice. Unlike Heat in which the audience can almost feel an almost existential dread bound to the disappointment of knowing both these men can’t win, so that one of these extremely well liked characters faces inevitable doom, the Fugitive has no shame in its game about fan service. It wants to give us what we want, the satisfaction of seeing neither of these men “lose”, and thus the impetus of the cuffs scene. Jones’s Gerard got his man, and his justice, Ford’s Kimble his freedom and respect. I mean his wife is still dead but , one thing at a time here.